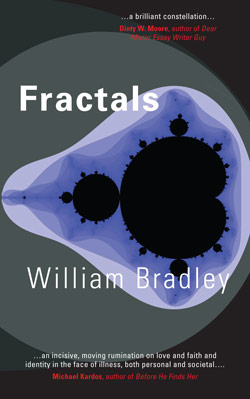

William Bradley, Fractals. Lavender Ink, 2015.

William Bradley’s work has appeared in a variety of magazines and journals including The Missouri Review, Brevity, Creative Nonfiction, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Fourth Genre, and The Bellevue Literary Review. He regularly writes about popular culture for The Normal School and creative nonfiction for Utne Reader. Formerly of Canton, New York, he lives in Ohio with his wife, the Renaissance scholar and poet Emily Isaacson.

About Fractals: In his seminal book The Fractal Geometry of Nature, Benoit Mandelbrot wrote, “A cauliflower shows how an object can be made of many parts, each of which is like a whole, but smaller. Many plants are like that. A cloud is made of billows upon billows upon billows that look like clouds. As you come closer to a cloud you don’t get something smooth, but irregularities at a smaller scale.” In this collection of linked essays, William Bradley presents us with small glimpses of his larger consciousness, which is somewhat irregular itself. Reflecting on subjects as diverse as soap opera actors, superheroes, mortality, and marriage, these essays endeavor to reveal what we have in common, the connections we share that demonstrate that we are all fractals, in a sense—self-similar component parts of a larger whole.

Buy the book here.

Julija Šukys: In Fractals you write of your numerous battles with cancer. It’s about remembering and forgetting; about scars both physical and psychological; about a loss of and then a return to faith (in another form). Finally, this book is also a kind of love letter to the women in your life: to your mother and wife who have sat beside you as you weathered storm after storm.

Thank you for talking to me about your book.

Fractals is a great title for an essay collection. A fractal is, of course, a never-ending pattern that repeats across different scales. Here, we see big and small essays, each of which circles similar but not identical territory to its adjacent texts. The collection has a looping structure or, as Benoit Mandelbrot described it, a cauliflower-like one. Can you talk a bit about how you pulled these pieces together and came to a final form? What was your guiding principle? Did you write any of the essays specifically for the collection? Can you tell us about essays that didn’t make the cut?

William Bradley: I didn’t know about fractals at all for the longest time. I was a very poor math student when I was a kid—it took me five years to get through three years of high school-level math because I kept failing—so I think maybe other people knew this stuff before I did. But once I did read someone referencing fractals, I started reading up on them even more, because I found the idea of the small thing containing the aspects of the larger thing kind of fit in with a belief system I was kind of clumsily assembling for myself—it seemed like it was Montaigne’s idea of each of us carrying the entirety of the human condition expressed in mathematical terms. So I loved that. I also loved the idea of each essay being a fractal, every book being a fractal. Once I started learning about fractals I started seeing them everywhere.

The book itself has taken many forms before I found the one that worked. Once upon a time, it was a much more conventional cancer memoir. I sort of gravitated away from memoir and towards essays in graduate school, though I didn’t realize I should be writing an essay collection and not a memoir for another several years.

I started writing an essay about fractals while also working on the cancer memoir, but it gradually seemed to me that some of the “chapters” in the memoir would work better as distinct essays, and that a lot of the “connective tissue” linking them together was actually pretty bad. So I got rid of that, and suddenly they seemed to have more in common with the essay about fractals—“Self-Similar” in the collection.

I do have other essays that at one point might have been part of the collection, but ultimately didn’t seem to belong. Some of these were more political, or were kind of off-puttingly angry, or just kind of argumentative. I’m working on another essay collection focused on masculinity and violence right now, and some of those seem to fit better with that collection.

In “Nana,” you explore the issue of writing and silence in a really thoughtful way. I’d like to have you share some thoughts on writers’ responsibilities to loved ones and ancestors.

“Nana” starts out:

I had promised my mother I wouldn’t write an essay about her mother until the old lady died. . . . [S]he made me promise that I would not reveal to the world that my grandmother had once, over a breakfast of coffee and English muffins, wished out loud that I would die in order to teach my mother a lesson about grief.

Just as we think you’re going to spill the beans (and you sort of almost do…), this essay ends up being about not writing the threatened piece (except that in not writing it, you’ve also already written it!). Can you talk a bit about negotiating with the dead and how you determine which silences to break, which secrets to keep, and which wounds it’s best to leave undisturbed? Do you have other ground rules for writing about your family, about your wife Emily, for example?

My biggest rule is that my essays are about myself—I don’t usually try to tell other people’s stories. Other people appear in my stories, but the reflection should always be about my relationship with them, my thoughts about them. So I might write about an experience my wife and I share, but I wouldn’t try to write about her relationship with her beloved grandmother, because that’s her story to tell.

But generally, I don’t think I need anyone’s permission to write about my own thoughts. That’s why “Nana” is written the way it is—all these things I don’t really know about my grandmother, but suspect may be true. In fact I recently talked to my mother about this essay and learned that I got most of it right, but some of it wrong—my grandmother did not find her father-in-law’s dead body, the way I thought she had. But her frustration with her husband’s refusal to talk about his suicide was real. But again, the essay really winds up being about my own desire to spare my mom’s feelings rather than the story of this troubled woman who said really mean things to people.

I didn’t actually set out to write an essay about my relationship with my mom when I started writing about what my grandmother said, but I actually learned a lot about myself as I was writing that very short essay.

You use the word “chrononaut” in your collection. I love this word – it suggests an image of writer as time traveler, but also as adventurer. “Cathode,” the essay that felt most like a trip back in time was for me, was amongst the most gutting in the collection (it felt like we were spying on a past version of you). In this piece you look back at a friendship – a not-quite-sincere friendship – with a boy in your youth. So much is intriguing about this text: its lack of resolution, its questioning of memory, and of the facts. The reader gets a sense of how the past versions of ourselves can seem foreign when we look back on them (ourselves). It’s infused with cringe-worthy regret and maybe even shame. Very powerful.

How did the essay come to be so short – was this its original form or did you whittle it down from something larger? Do you think its power comes from its form? (I do…)

Oddly enough, given the essay’s preoccupation with memory, I don’t remember how I went about writing “Cathode.” I think maybe some magazine or journal had a call for essays about memory, and I came up with this idea of my memory being like an old television set where the picture slowly came into view. But I also think I was probably trying to imitate Nabokov, who wrote about memories being projected onto a movie screen.

And yeah. That essay’s really about my own shame at how cruel I could be as a kid, even though I thought I was the hero of the story I was writing for myself. I think most boys are probably similarly cruel—even when we see someone in pain and know we should offer some type of support or comfort, we don’t because we don’t want to become the ones who are picked on or ostracized. Or at least that’s how it felt for me.

It was definitely designed to be short. I don’t think the idea of the television image that sort of bookends the essay would work if I’d put, like, 3,000 words between those sequences. And it’s true that I don’t really remember much of the event—just the image of this sad boy making an obscene gesture at the kids who are supposed to be his friends, and the feeling that I should have been nicer.

Why did you call this text “Cathode”?

I don’t really remember why I titled the essay “Cathode,” but I suspect it was because I liked the idea of my memory working like an old cathode ray tube television set, like the one I’m watching towards the end of the essay. I do remember looking up old television sets and how they worked, and obviously something about the word “cathode” appealed to me. I think because it’s something I associate with a past that I’m sometimes nostalgic for but that I know wasn’t actually better than the present moment (in much the same way that cathode ray televisions are not, in fact, better than the LCD and plasma screen televisions we have today).

Given the book’s obsession with the pop culture I watched on old television sets– soap operas, game shows, horror movies– it seems kind of appropriate for the entire book, too, though I admit that idea just occurred to me because you asked about it.

Continue reading “CNF Conversations: An Interview with William Bradley”

![photo[3]](https://julijasukys.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/photo3.jpg)