I’m home.

Two cousins and I spent fourteen days travelling from Lithuania to Siberia’s Tomsk region, in search of the neighbouring villages of Brovka and Bialystok where my grandmother lived in forced exile and worked on a collective farm for seventeen years (for a time she lived in one village, then in the other).

We found both villages (Bialystok still very much alive; Brovka now defunct), plus so much more along the way.

Siberia surprised me at every turn. It was both gentler and at times more desperate than I’d imagined. The journey was worth every minute and every kopeck.

In Tomsk we marvelled at stilettoed women strolling through the city with their babies, and were awed by the beauty of Tomsk’s Catholic Church perched up on the city’s one hill. The nearby Sisters of Charity welcomed us warmly and glowed with joy, all the while telling harrowing drunk tank tales. Six nuns minister to the city’s alcoholics.

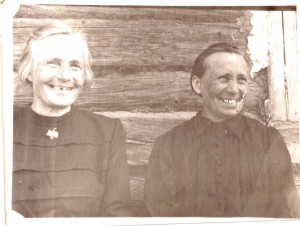

We had many local companions and guides without whom the journey from Tomsk north to Bialystok would have been impossible: there was Vasily, the museum director, born and raised in the village; Svetlana, our guardian angel, daughter of a Lithuanian exile, and generally the coolest Siberian you’ll ever meet; 79-year-old Anton who took us into his house and fed us from his kitchen garden; Dusya, Anna and Nina, who shared their memories of our grandmother; and Maria who showed us hospitality with a potato and egg fry that we ate straight out of the skillet plonked down in the centre of the table, Siberian-style.

All this, plus my impressions of Moscow suffocated by wildfire smoke, our deportation from Belarus and resulting mad-dash through Copenhagen’s airport in a race to catch up to our train, and of the still Siberian landscape under the blue shutters and fences of Russian villages, will unpack and reformulate itself into a book over the next year or so.

I’ll share what I can as I work.

To all those who helped along the way: Spasibo bolshoe. Ačiū.

This is only the beginning.

[Photo: M. Angel Herrero]