Mary Cappello, Life Breaks In (A Mood Almanack). University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Mary Cappello is the author of five books of literary nonfiction, including Awkward: A Detour (a Los Angeles Times bestseller); Swallow, based on the Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body Collection in Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum; and, most recently, Life Breaks In: A Mood Almanack. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Salon.com, The Huffington Post, on NPR, in guest author blogs for Powells Books, and on six separate occasions as Notable Essay of the Year in Best American Essays. A Guggenheim and Berlin Prize Fellow, a recipient of The Bechtel Prize for Educating the Imagination, and the Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize, Cappello is a former Fulbright Lecturer at the Gorky Literary Institute (Moscow), and currently Professor of English and creative writing at the University of Rhode Island.

About Life Breaks In: Some books start at point A, take you by the hand, and carefully walk you to point B, and on and on.

This is not one of those books. This book is about mood, and how it works in and with us as complicated, imperfectly self-knowing beings existing in a world that impinges and infringes on us, but also regularly suffuses us with beauty and joy and wonder. You don’t write that book as a linear progression — you write it as a living, breathing, richly associative, and, crucially, active, investigation. Or at least you do if you’re as smart and inventive as Mary Cappello.

What is a mood? How do we think about and understand and describe moods and their endless shadings? What do they do to and for us, and how can we actively generate or alter them? These are all questions Cappello takes up as she explores mood in all its manifestations: we travel with her from the childhood tables of “arts and crafts” to mood rooms and reading rooms, forgotten natural history museums and 3-D View-Master fairytale tableaux; from the shifting palette of clouds and weather to the music that defines us and the voices that carry us. The result is a book as brilliantly unclassifiable as mood itself, blue and green and bright and beautiful, funny and sympathetic, as powerfully investigative as it is richly contemplative.

“I’m one of those people who mistrusts a really good mood,” Cappello writes early on. If that made you nod in recognition, well, maybe you’re one of Mary Cappello’s people; you owe it to yourself to crack Life Breaks In and see for sure.

“Are we sometimes not astonished by the beautiful futility of encountering some sudden fugitive moment that renders us so vulnerable to ‘unanticipated forms’: of perhaps an inner light or an inner dark? Here, with Mary Cappello’s ravishing prose, lies a vibrating scalpel that intricately parts the belly of little swirling vertigos that we have no name for but know so deeply.”

— The Brothers Quay

“Mood is alpha and omega, it is everything and nothing” – Mary Cappello, Life Breaks In

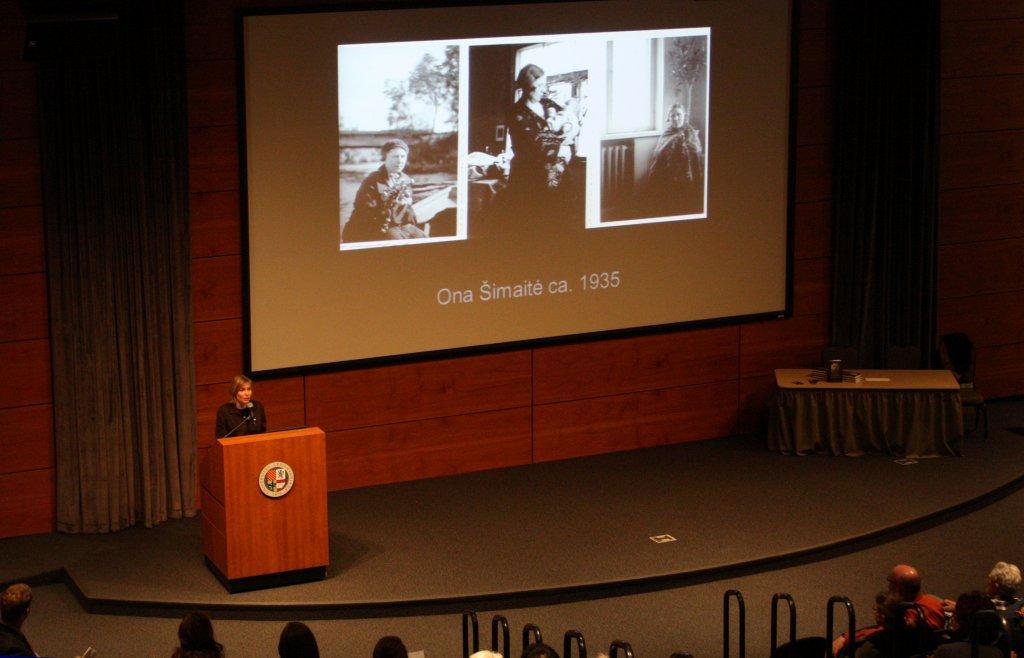

Julija Šukys: Mary, first of all, congratulations on your book. Life Breaks In is learned, rigorous, and, at times, intimate and devastating. On the one hand, the text is incredibly wide-ranging: you take the reader through subjects as varied as Joni Mitchell’s music, mood rings, your father’s darkness, your friend’s death from cancer, taxidermy, and the weird queer history of children’s books. But on the other hand, your book is impressively focused and disciplined as it continually loops back to thinking about mood as sound, as space, as reading, as color. It does so in an almost oblique way and manages to look closely at something that is otherwise almost invisible.

You have written that the challenge of the book was “not to chase mood, track it, or pin it down: neither to explain nor define mood – but to notice it – often enough, to listen for it – and do something like it without killing it in the process” (15). It seems like mood is something that you can only see through the prism of something else, like those ghosts in children’s cartoons that become visible in the dust beaten out of a chalkboard brush. Can you say a little bit about how you came to your subject? And can you talk a bit about the title, Life Breaks In, and the role that rupture plays in a meditation on mood?

Mary Cappello: This question of how we come to our subjects is perpetually intriguing to me. Some subjects for me have been urgent givens (for example, cancer); others, I’ve arrived at through intricately circuitous routes even though, once there, they greeted me with a kind of “ah-ha” or “but-of-course” feeling (e.g., awkwardness); still others were the result of an accidental encounter, what Barthes might call a “lucky find,” almost like a punctum in photography (e.g., the Chevalier Jackson foreign body collection). Mood happened for me in yet another way—in its own way—and it was as though it was always hovering. The subject has played around the edges of my consciousness for many years, and, by the time I brought the book to completion, it felt as though it was the work toward which all of my work had been tending.

Sometimes I’ll be reading a book I’ve read a thousand times, and I’ll find marginalia that I wrote in it dating back twenty years relative to mood. I guess I’m trying to say that mood felt to me like the thing I’ve been writing about all along but that had never announced itself as such—which makes me wonder if this is a sort of experience relevant to all writers. Unlike my other ostensible “subjects,” mood seemed to be following me rather than vice versa.

The title is a phrase lent to me by Virginia Woolf who wrote these wonderfully suggestive lines in one of her diary entries: “How it would interest me if this diary were ever to become a real diary: something in which I could see changes, trace moods developing; but then I should have to speak of the soul, & did I not banish the soul when I began? What happens is, as usual, that I’m going to write about the soul, & life breaks in.”

I’m really interested in the time/space that mood exists in—I mean, moods seem to be a bedrock of our being (we’re never not in a mood of one sort or another), at the same time that moods seem to exist quite apart from our ability to perceive them. Are moods co-terminus with the thing we call “life” or “living”? Does life interrupt mood or do moods interrupt life? This is related to the aesthetic problem that you refer to in your question—I mean, here’s this thing that is ephemeral, amorphous but ever-present and foundational. It will not let you pin it down, and it might only come into view when you aren’t trying to discover it. If you look too directly at it, it may not show itself, or will vanish. And the minute it does materialize, life is sure to break in, and poof, it’s gone.

I hope that readers take pleasure in the unexpected ways in which breaks enter in to the book, and I’d hardly exhaust those ways if I mentioned just a few, like day break and breaks in clouds; breakthroughs and heartbreaks; the breaking of a silence and the breaking into song.

As you know, I read this book very slowly, in fits and starts. At first, my pace embarrassed me (confession: I’m a slow reader at the best of times), but the deeper into the book I got and the more I thought about what you were doing in it, the more I made peace with my meandering methods.

You’ve subtitled the book “A Mood Almanack” and elucidate it like this: “the almanack is a revelatory book and a book of secrets. A book whose tidings we look out for and consult from time to time…. A book to wander in a desert with…. A book whose only requirement is that we float into and out from the streets where we live, pausing long enough to feel the mood beneath us shift.” (16) It occurs to me now that this is a book that values the slow reveal and invites a reader to go off, wander around, and return according to her inclinations (or, indeed, mood).

Can you say a little more about your notion of the book as almanack? (By the way, my autocorrect keeps trying to remove the k at the end of that word!)

All that I can say about the slow reveal is: yes, yes, yes. Meandering methods, both in writing and in reading, yes. I’m so glad that this is how you experienced the book, Julija. I seem to have found my ideal reader!

Mood called for what I describe as “cloud-writing,” which asked for an aesthetic of hover and drift. Like my second book, Awkward: A Detour, this book can be dipped into, read front to back, or not. For the reader interested in moving front to back, the book is structured to allow for various more and more voluble returns (as you note in your opening lines here), and a frame tale relative to voice and mood (most especially, the role of the voices of our earliest caretakers, how we may have come to receive those voices and, if we grew up to be writers, how we later constructed voice-imbued atmospheres in the form of writing).

I had a lot of reasons for calling the book an “almanack,” and with that older spelling, too. I wanted to nod in the direction of those early autobiographical experiments of Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack, but also the less well-known book by Djuna Barnes, her Ladies Almanack (1928) and its wonderful sub-title, “showing their Signs and their Tides; their Moons and their Changes; the Seasons as it is with them; their Eclipses and Equinoxes; as well as a full Record of diurnal and nocturnal Distempers, written & illustrated by a lady of fashion.”

Formally, though, the “almanack” appealed to me for its generic specificity and range: an almanack (especially a “farmer’s alamanack”) shares a kinship with mood-writing because it’s a place we turn to for chartings of weather patterns and cloud movements, the prospect of a good harvest or a drought, and it’s a space where different types of knowledge on a subject can intermingle, where folk wisdom meets philosophy, aphorism and recipes coincide—more to the point, where a kind of non-knowledge or useless knowledge (à la Gertrude Stein) prevails. I didn’t structure the book like an almanack—this would have felt artificial to me—but when I learned more about the etymology of the word, I couldn’t believe how fitting it was for a mood-book: from classical Arabic, munaāk, it refers to a place where a camel kneels, a station on a journey or the halt at the end of a day’s travel. Simultaneously, it derives from cognate Arabic words for “calendar,” and “climate.” This blew my mind because it seemed to bring together so many mood-relatives: temporality, charts and unchartability, atmosphere, rest and pause. There is also a warmth to the Farmer’s Almanack that I was hoping to invoke.

Continue reading “CNF Conversations: An Interview with Mary Cappello”