La varicelle, as it’s called around these parts, or chicken pox to us English speakers. Our doctor confirmed it this morning. Despite my son’s vaccine against it, the virus has taken hold, though perhaps not as firmly as it might have otherwise.

As I write, my red-spotted boy colours beside me with his new markers, picked up at the pharmacy with his prescription. There’s nothing like sickness to make you appreciate your good health and the time you have to work under more normal circumstances. The coughing and sneezing of the past few weeks have been a good reminder to me that, when the body fails, a life of the mind is hard to sustain.

If I want my mind to function, I have to honour my body.

I’ve always had a bad back, and if I write for too long without taking the time to go to my yoga classes, it isn’t long before the pain takes over and saps all my attention. I learned this the hard way some ten years ago, when I sat at my desk from dawn till dusk, seven days a week, five weeks in a row, to finish my dissertation. By the end of it, I could barely walk. Poor me.

But recently, I’ve been trying to think about my back pain differently. I’ve started thinking of it as a gift.

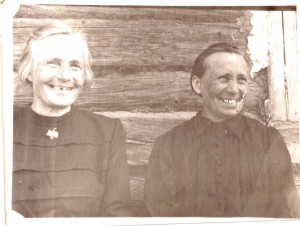

I inherited my bad back from my father, who in turn got it from his mother. And when I speak to my cousins and aunts, we are all surprised hear that we have the same issue. Back pain binds us together in the present, but it also gives us a link to the past – to the grandmother who connects us all, and who inevitably had a whole different relationship to pain.

The fact is that my back pain is but a shadow of what my grandmother went through. Whereas I have the luxury of taking a break and heading to yoga class when I feel my muscles acting up, my grandmother had no such choice. Whereas I have the time to think about this pain, to manage it, and to turn it into a text if I can find the right words, my grandmother had to grit her teeth and keep going.

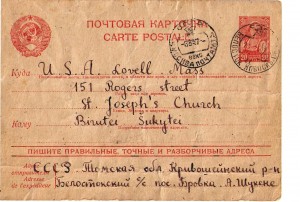

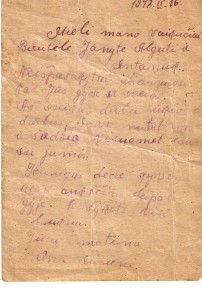

There were calves to feed, cows to milk, logs to chop, and there was no rest for her aching back. On the farm where she worked (for nothing), in a place she had been exiled to against her will, back pain would have meant something very different to her: pure suffering and an external manifestation of what must have been happening inside her.

This coming weekend (as long as the pox allow – our doctor is hopeful), my son and I will travel to meet with my cousins, their children, and my aunt. Darius, who travelled with me to Siberia to find my grandmother’s village, will come up from San Francisco to meet us on his holiday weekend, and has planned a traditional American Thanksgiving dinner for the occasion.

As I raise my glass to toast the harvest and the gathering of my grandmother’s children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren for the purpose of hearing stories about and looking at pictures of the place she was exiled, I will remember my minor annoyances. And I will be thankful for the pox and the pain.

Because my trials are so small, I know I am blessed. In this troublesome back of mine, I will always carry of piece of my grandmother.

[Photo: Sara Björk]