I’ve been working with letters as literary artifacts for just over a decade now. As a graduate student, my attraction to letters was instant. The very first time I sat down with stack of yellowing missives, I was hooked, and never looked back.

I work with letters because I like the intimacy they afford. Piecing a story together through an unexamined correspondence is a way to tap into untold stories and to break new ground. Reading letters also gives me a glimpse into the ways in which people meld writing and life and make sense of their time on earth. And I’m interested in the ways the big and small combine in letters — how, for example, a letter can give a ground-level view of historical events.

But as we increasingly eschew handwritten letters on paper for electronic correspondence, the materials I use for my research are becoming a bit of dinosaur. I myself have boxes of love letters written on lined notebook paper from when I was a teenager, but mine may be the last generation to be able to say this.

And as I embark on the writing of my third book — my second to use letters as a primary resource — I realize that it’s time to start reflecting not only on what letters say, but on what they are.

I’ve never really cared all that much about physical objects in my work. Whether I read a second-hand copy, a library copy, or a first edition of Gertrude Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, as long as all the pages are intact, it’s all the same to me. It’s why I could never be an art historian, because the value of objects that interest me has little to do with money, or physical uniqueness.

But now I see that it is no longer enough simply to consider the content of the letters I work with. Because letters are on their way out as a cultural practice, I will inevitably have to start reflecting more seriously on their physical form, the way they travel from sender to recipient, and how the process of letter-writing differs from or in some ways resembles the way we communicate today.

National Public Radio has kick-started this thinking process for me. It’s currently doing a series on the United States Postal System, which is apparently in deep crisis. As part of its Postal series, NPR has curated an on-line exhibit of interesting pieces of mail, called “Mailed Memories: Your Cherished Letters.”

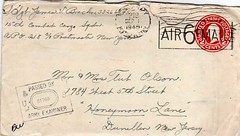

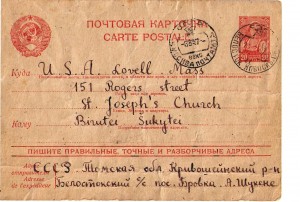

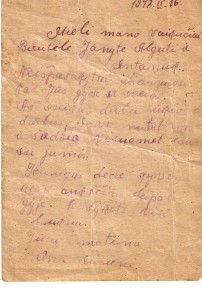

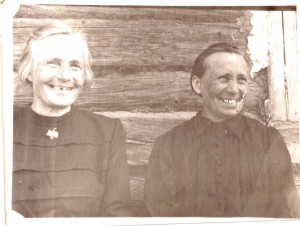

The exhibit includes images of an annual cake-package sent by post, a posthumous birthday card, and a postcard sent to a kid by Allen Ginsburg that was originally addressed to John and Yoko. The last piece in the exhibit is my contribution: a 1947 postcard sent from Siberia to the US by my grandmother. Its tagline: “Finally, a letter from mom.”

It is indeed a cherished piece of mail, and I’m honoured to have it used as part of the piece. You can see the exhibit here.

I rarely write letters anymore myself, and wonder if others do. Share your letter-writing and -receiving stories with me through in the comments section. I’m interested to know about your writing life.

[Photo: Sea Dream Studio]