Nancy K. Miller. What They Saved: Pieces of Jewish Past. University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

*

This is Part II of a two-part interview. Click here to read Part I.

Julija Šukys: I loved reading your descriptions of how you related to “The Old Country” before this quest. “Russia, a vast faraway, almost mythical kingdom ruled by Czars, was filled with mean peasants, who lived in the forest with wolves [. . .]. Basically, Russia was a place one left, if one was a Jew, as soon as possible” (36).

As you begin to piece your family’s past together, you start to see a much more nuanced picture. Your family, it turns out, comes not from this fictionalized Russia, but from Bessarabia, present-day Moldova. Thus “The Old Country” morphs into a real place. You learn too that your family likely lived a middle-class life rather than a shtetl existence as you’d imagined. How did this process of discovery and understanding change your thinking about both about your Jewish past and your American present?

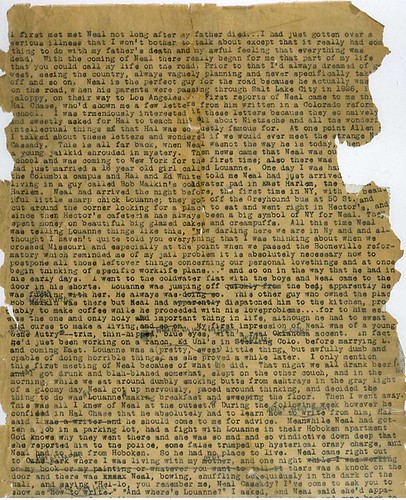

Nancy K. Miller: Like many third-generation descendants, I had pictured my ancestors as Jews from Eastern Europe were portrayed in Fiddler on the Roof. What other image was there? It took my second trip to Moldova to understand that my paternal grandparents were already modern, Westernized, and to some degree distanced from Orthodoxy (my grandmother was not wearing a wig, my grandfather trimmed and then shaved his beard): city dwellers and not living with goats. True, as Jews, they were subject to pogroms—and probably witnessed the famous pogrom of 1903 that took place in Kishinev (now Chisinau, the capital of Moldova) where they were living before emigrating in 1906, but they were not peasants; nor were they wealthy (alas). At the same time, their decades on the Lower East Side of Manhattan—where my father grew up—had to have deeply influenced my father’s tastes, and ultimately mine. When I was in Kishinev, for instance, I was amused to be served “mamaliga” (polenta), a Moldovan specialty–one of my father’s favorite foods and that he made for himself when he was living on his own after my mother’s death. I saw my father as both more Jewish—and less. In other words, he did not “lay” tefillin, he and my mother joined a Reform synagogue—horrifying my mother’s parents—but he saved what his mother had saved, the traces of their immigration. I now see myself as an inheritor of that history, not purely American, unless we understand American as always marked by ethnicity and coming from another place, never fully belonging.

I was very interested to read your book for purely selfish reasons: I too am writing a sort of family history largely based on a collection of letters that my grandmother sent to her children from Siberia. A constant preoccupation as I write this story is whether or not anyone outside of my immediate family will or should care about this narrative I’m piecing together. I imagine it’s the preoccupation of anyone writing a book based on private and invisible lives. Was this the case for you? How did you work through this question of why this story matters, and what conclusions did you draw about what family stories and private histories can teach us?

Indeed, I was tormented by the “so what” that all autobiographers grapple with. Why should anyone care about these people? The way I convinced myself that readers could care was by trying to show their story as representative—generational and historical. But beyond that, and only readers can say whether I succeeded in wrestling with this paradox, I tried to bring out the less specific, more universal aspects of my quest: wanting to know the story of one’s origins, who our parents were before we were born, where our grandparents came from, how we always come so late to wanting to know, and therefore not being able to ask. I confess that I’m always thrilled when someone who isn’t Jewish, who isn’t from an immigrant past, connects to the story as just that: the attempt to grapple with the past, with incomplete memories, with loss, with absence. I don’t expect anyone to care about my dead ancestors—as people, I’m not sure I did, either—but I hope that readers will relate to my desire to discover them, and the importance of finding out whatever one can. The book is a celebration of knowledge—maybe that’s because I’m an academic at heart. I guess that’s the lesson: there is so much to be learned, it behooves us to search for it. The search itself is probably the most important aspect of my book.

A major theme of this book is the absence of children. You are the last in your father’s line, and therefore there is no one to inherit these objects. It seems to me that your book is a kind of meditation on life, aging and death. Can this book take the place of the heir? Even if there is no child to inherit the dunams, there are the story and map of them, and these will never die. To what extent is writing about the family archive a way of creating non-biological continuity?

Yes, I hope that this book can take the place of the heir—even though I also know that that is impossible. I have found some consolation in having turned the objects into language, put them as words on the page, even though after I die, no one will want them, keep them, save them. That is a sadness but a fact of life, of my life, anyway. So it’s true that the book meditates on the meaning of loss and expresses the mad desire to hold on to whatever remains as traces of what we have lived.

The book ends with the acceptance that some things are unknowable. You can’t connect all the dots. You can’t know what caused a seeming rift between your father and his brother, but “a story about finding always returns to the places where the story got lost. It’s also a chance to begin again.” How does this new beginning look for you now that the book has appeared?

Well, for one thing, I have a different, richer view of my childhood, which always seemed mysteriously unhappy and vapid—standard issue professional, middle-class New Yorkers. But it’s not only about the past. I also feel newly excited to experiment as a writer. To circle back to your first question, in my mind, I’ve created a book about objects, from objects. I had no clue about how I was going to write this book until I did. So I look forward to my next projects emboldened by the adventure.