The notoriously unrewarding business of writing non-fiction

books in Canada gained a double dose of glamour and money

yesterday with the announcement of the $60,000 Writers’

Trust Hilary Weston Prize. Billed as the richest award for

factual writing in Canada, the prize and the autumn gala at

which it will be announced are intended to do for the craft

what the Giller Prize does for Canadian fiction in the busy

fall season, according to its founding sponsor, the former

Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario.

Citing the work of Northrop Frye, Marshall McLuhan, Jane

Jacobs and Margaret MacMillan while making the announcement

in Toronto at Holt Renfrew, the Weston family’s store,

Hilary Weston said she hoped the prize would help revitalize

a form of writing that is becoming increasingly difficult to

undertake in Canada. “As I get older I really feel

passionate about non-fiction because of its broad reach,”

she said, adding that the prize is intended in part to

underwrite the enormous research the best non-fiction books

require.

Weston’s commitment transforms the unsponsored orphan of

the Writers’ Trust awards program into a sparkling

Cinderella with an appropriately glamorous coming-out next

fall, in the same few weeks when winners of the group’s

own fiction prize, the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the

Governor-General’s Literary Awards are announced. Unlike

the remainder of the Writers’ Trust prizes, which are

typically presented as a group at a low-key ceremony, the

Hilary Weston Prize will get its own gala, potentially to be

televised by CBC.

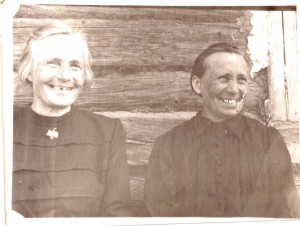

[Photo: Stephen A. Wolfe]