Few aspects of nonfiction cause as much anxiety for beginning (or even experienced) writers as writing about family. Memoirists and essayists approach the issue of familial input or approval in a variety of ways. Some writers give family members veto power over their manuscripts. Others only share their books in proof—that is, before they are published but after they are typeset, when it’s too late to change a text significantly. Still others share nothing at all, and keep a text close until its publication.

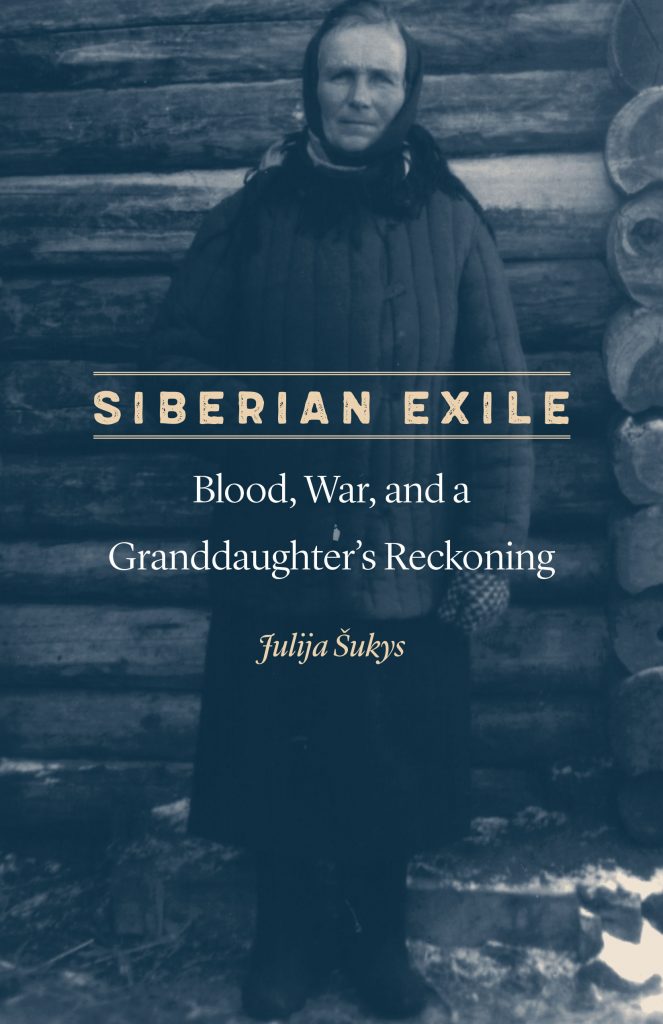

For better or worse, I fall into this last category: though I told family members what they could expect to find in my 2017 book Siberian Exile: Blood, War, and a Granddaughter’s Reckoning, no one (except perhaps one beloved cousin?) got to read the text in advance. And no one (not even the beloved cousin!) got veto power over the book. Though, to be fair, no one asked for such power either. Maintaining this level of control over one’s work makes the writing process easier (the last thing a book needs is a whole bunch of cooks), but it also makes publication day nerve-wracking as all heck.

When I started work on Siberian Exile, I planned to write the story of my grandmother Ona’s seventeen years of life and work on a Soviet special settlement in the Tomsk region of Russia. The book was going to be a kind of testament to her survival and an exploration of women’s memory, oral history, storytelling, and life-writing. It was going to focus on her almost exclusively.

I was forced to widen my scope in 2012, when I requested, among other materials, my grandfather’s KGB files from the Lithuanian Special Archives. With those documents came a bombshell that I couldn’t ignore. The files accused my grandfather Anthony of overseeing a massacre of Jewish women and children. They also showed that he had been under surveillance by Soviet authorities for most of his life in postwar England and Canada.

Suddenly, my female-focused project morphed into a painful text of reckoning with a dark family secret. Rewriting my family’s past in this way felt like stepping into a storm. The reader I was most worried about? My late father’s elder sister, Aunt B. The sole surviving member of Ona and Anthony’s nuclear family of five.

Aunt B. has always had a sharp edge. She can be quick to criticize and will not hesitate to tell you the truth, no matter how thorny, right to your face. I too can be quick to criticize. I get into trouble for speaking without thinking. Point is, we aren’t all that different. Point also is: two sharp tongues can draw a lot of blood.

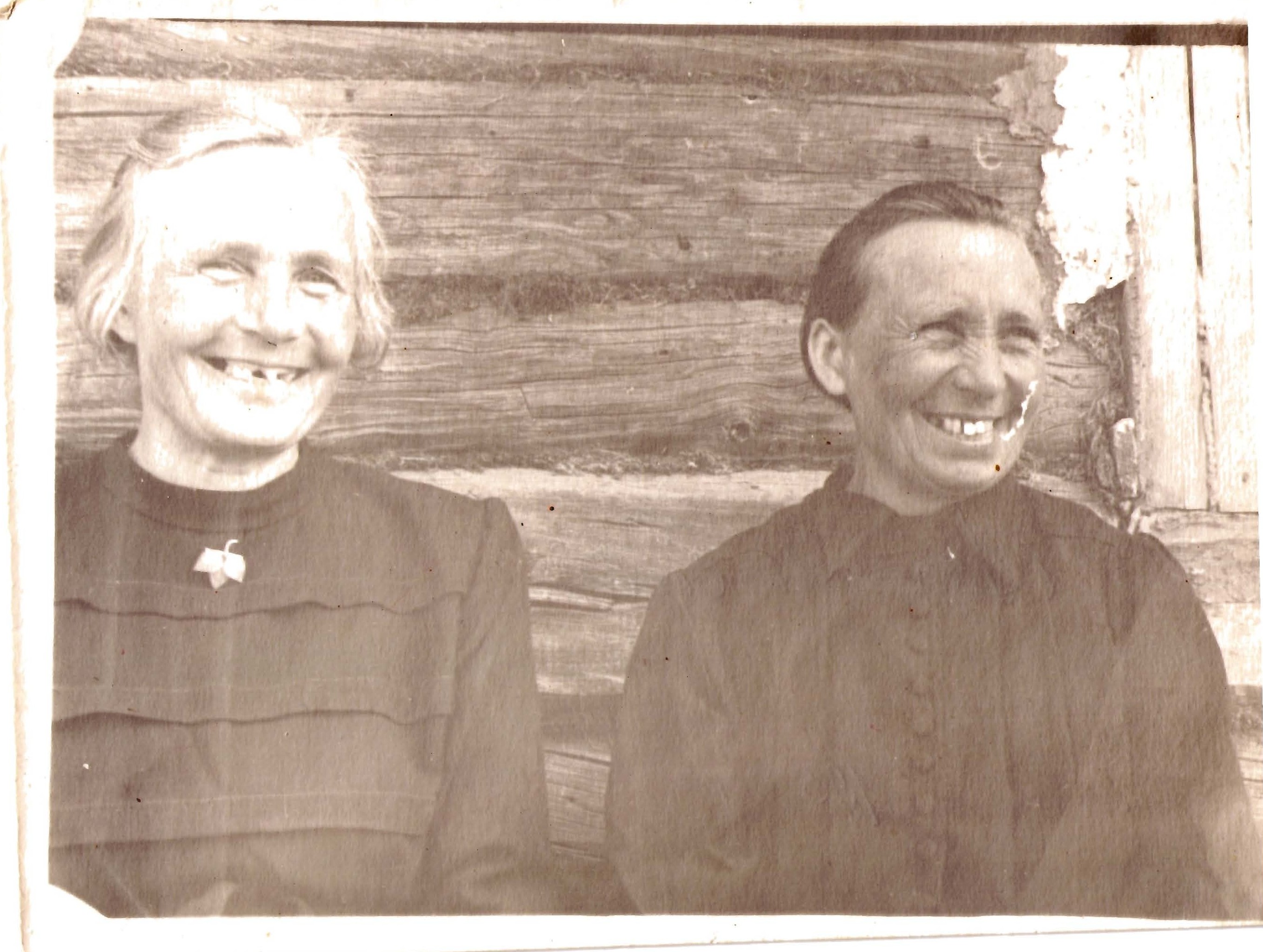

For most of my life, my relationship with Aunt B. was polite and cordial, but not close. This changed when I began to write about our family. The project gave us a chance to bond over a shared purpose and, over time, I began to feel our mutual sharpness soften. She and I started spending hours at her kitchen table, looking at photographs, talking about life in the displaced persons camps and how it felt to meet her mother when she finally arrived in Canada, after so many years of separation. We took to talking on the phone regularly. I liked that Aunt B. and I were partners in this, so I began sending her updates on my work.

For most of my life, my relationship with Aunt B. was polite and cordial, but not close. This changed when I began to write about our family. The project gave us a chance to bond over a shared purpose and, over time, I began to feel our mutual sharpness soften. She and I started spending hours at her kitchen table, looking at photographs, talking about life in the displaced persons camps and how it felt to meet her mother when she finally arrived in Canada, after so many years of separation. We took to talking on the phone regularly. I liked that Aunt B. and I were partners in this, so I began sending her updates on my work.

But Aunt B. and I never talked much about Anthony. The subject of the Holocaust in Lithuania and the role he played in it was simply too painful, too delicate. It was easier for me to put his part of the story onto the page than to speak it out loud. Without ever explicitly agreeing to do so, Aunt B. and I established a sort of equilibrium, bonding over Ona’s story and carefully sidestepping Anthony’s.

Of course, our dance of avoidance couldn’t last forever. Eventually, the book would come out and my aunt would read it. The notion terrified me. Just thinking about it made me queasy and kept me up at night. I worried the book would hurt her. That her sharpness would return. That our newfound relationship would suffer, and that she would disown me.

“You’re not giving her enough credit,” said my cousin Darius when I confessed my fears to him. “Send her a copy of the book.”

So I did.

I inscribed the title page, slipped in a note of thanks for her support and help, and then packed it all up, posted it, and waited.

After about ten days, the phone rang and her name popped up on the caller ID. I swallowed hard and picked up the receiver. Aunt B. had read Siberian Exile in a single sitting, she told me, on the very day it arrived. “I loved it,” she said.

I was stunned.

“She said that?” my cousin Darius said in disbelief, when I called him to report the surprising turn. “What did you say?”

“That I was just happy we were still speaking to one another. I mean, I did compare her father to Adolf Eichman. Do you think she read that part?” Darius—my biggest champion and eternal optimist—laughed and laughed.

About two weeks later Aunt B. called me again. She had read the book three more times, she told me, and in this call, her assessment was more nuanced. “I don’t see my father exactly in the same way as you do, and I don’t agree with everything you write,” she said, “but I still love the book. This book is a gift.” I paused before responding. After a moment of thought, I thanked her for being so generous. I told her I understood her perspective. She saw things differently, and that I was OK with that.

“He was my father,” she said quietly. “You never knew him like I did.”

“No,” I said. “That’s true.”

We talked for a while longer, and soon our conversation turned to weather reports, summer plans, and teaching schedules. I told her some funny pet stories and she told me about the state of her yard. Ultimately, we ended the call like any other and, as I hung up, I realized that we’d succeeded. The danger had passed. We had come through the storm intact. We had kept control of our tongues.

There is, of course, no guarantee that loved ones will accept or like or even respect what we write. But as writers, perhaps we have no choice but to trust not only our books but also our readers, even the ones whose opinions scare us the most. If we’re lucky, our books will do their jobs, and our most unnerving readers will open themselves up to them. And finally, if we’re gentle and patient, these same readers may surprise us and respond to our words with love.

Originally published on the University of Nebraska Press’s Blog.

[Photo: PracticalCures.com]