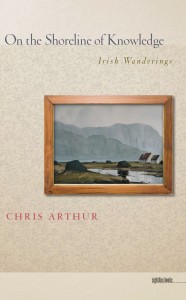

Chris Arthur, On the Shoreline of Knowledge: Irish Wanderings. Iowa City: Shoreline Books, 2012.

The carefully crafted, meditative essays in On the Shoreline of Knowledge sometimes start from unlikely objects or thoughts, a pencil or some fragments of commonplace conversation, but they soon lead the reader to consider fundamental themes in human experience. The unexpected circumnavigation of the ordinary unerringly gets to the heart of the matter. Bringing a diverse range of material into play, from fifteenth-century Japanese Zen Buddhism to how we look at paintings, and from the nature of a briefcase to the ancient nest-sites of gyrfalcons, Chris Arthur reveals the extraordinary dimensions woven invisibly into the ordinary things around us. Compared to Loren Eiseley, George Eliot, Seamus Heaney, Aldo Leopold, V. S. Naipaul, W. G. Sebald, W. B. Yeats, and other literary luminaries, he is a master essayist whose work has quietly been gathering an impressive cargo of critical acclaim. Arthur speaks with an Irish accent, rooting the book in his own unique vision of the world, but he addresses elemental issues of life and death, love and loss, that circle the world and entwine us all.

“Chris Arthur is among the very best essayists in the English language today. He is ever mindful of the genre’s long literary tradition and understands—as did his great predecessors—that the genuine essay is grounded in the imagination, in our quest for art and beauty, as deeply as is poetry or painting. Every young writer who wants to experience the creative possibilities of the essay form must read Chris Arthur—it isn’t an option.”—Robert Atwan, series editor, The Best American Essays.

Chris Arthur lives in Fife, Scotland. He has published several books of essays, including Irish Nocturnes, Irish Willow, Irish Haiku, Irish Elegies, and Words of the Grey Wind. His work has appeared in Best American Essays, American Scholar, Irish Pages, Northwest Review, and Threepenny Review, among others. He is a member of Irish PEN, and his numerous awards include the Akegarasu Haya International Essay Prize, the Theodore Christian Hoepfner Award, and the Gandhi Foundation’s Rodney Aitchtey Memorial Essay Prize. Visit www.chrisarthur.org to find out more about the author and his writing.

Julija Šukys: Your essays often take the meditation of familiar objects as their starting points. For example, you reflect on a seed found in your mother’s coat pocket and use it as way of contemplating her passage and of wondering about sides of her personality that you never saw. In essays that follow that first (I must say, masterful) piece, you take a pencil, a family painting, your father’s briefcase (a varied “silent symphony of objects”) as starting points. Your contemplation of these things then takes you on journeys of remembrance, of speculation, of mourning, and of historical clarification (by this I mean the ways in which you translate the Troubles and your experience of growing up in Ulster through seemingly trivial material objects and inconsequential places). The result is this incredibly rich and dense collection, On the Shoreline of Knowledge. I confess to being a slow reader on the best of days, but it took me forever to finish your book. This is not a because of some fault in your work, but rather a function of its density and richness. Each essay is a kind of polished stone, or perhaps like that drop of dew you write about with so many images and stories contained within it. Congratulations on an extraordinary accomplishment.

This past fall, I’ve been leading a writers’ workshop on the personal essay. We’ve talked a lot about the ways in which the best essays contain the large and the small – or rather the large within the small. Your essays seem to me to be some of the most dramatic illustrations of the principles that I’ve come across. I wonder if you could talk a little about your approach to writing and thinking your way from the small to the big and back again.

Chris Arthur: I’m fascinated by what I suppose you might call the dual nature of things – though that’s something of a misnomer. The duality is more apparent than real and lies in us, and how we observe things, rather than in the things themselves. I guess in some ways it’s a kind of defense-mechanism to stop ourselves being overwhelmed. What I mean by dual nature is the way in which something can be seen in such different perspectives, how we can measure it according to such enormously varied scales. For instance, my first book, Irish Nocturnes (1999) begins with an essay entitled “Linen.” Its point of departure is a small piece of embroidered linen cloth. At first glance it seems entirely ordinary – something easily overlooked or just dismissed as uninteresting. But when you start to examine it, think about it, you’ll find that it’s densely packed with all sorts of interrelated stories – the story of flax and its cultivation; the story of the individual who made it; the story of linen manufacture, in particular the ways this developed in the part of Ireland where the piece of linen is from; the story of the metaphors and symbols that can be derived from linen; the story of this fabric’s use from ancient times until the present. Teasing out some of the storylines embedded in this one small piece of cloth you soon find far wider vistas opening up than are immediately apparent when you first look at it.

I was pleased that a reviewer specifically flagged up the way “Linen” moves from the small-scale to the large-scale. Writing in The Literary Review (Vol. 44 no. 3 [2001], pp. 602-03) Thomas E. Kennedy said this:

I started the first essay, “Linen,” with a fear that I would be subjected to one of those wearying parsings of technique too often serving as essays (how neon is made; how the horned beetle mates), in which one learns industrial or biological detail one is never likely to have use for and which, in the words of Dylan Thomas, “tell us everything about the wasp but why.” But no, Arthur moves from the tradition of linen to the strands of history and the sorrows of those who have come before us—a movement back in time that he conjures on the flying carpet of a single piece of antique linen … In a mere fourteen pages we have surveyed the history of mankind through a piece of stuff that lies beneath the author’s computer, and we—I—find a new way to meditate existence.

Of course it’s not just bits of linen that offer the essayist flying carpets by which to get to interesting places. All sorts of objects and experiences have this same potential. In fact I’m almost tempted to say that everything has. I love John Muir’s comment that “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” From an everyday, commonsense perspective, of course, we turn our back on Muir’s insight and behave as if we can consider things singly and separately. My essays are in the business of reminding us about their hitching to everything else. I try to highlight and follow for a way some of the intricate mesh of connections in which things are embedded.

Your point about essays containing the large within the small is a good one and points to an important theme in many essayists’ work. But moving between the scales is not something I try to do consciously. I don’t have to think my way from the small to the large and back, its more like noticing a rhythm or a dynamic that seems implicit in things – or in the way I see things. It’s almost like the heartbeat of perception. Maybe writing essays is a kind of taking of this pulse.

I’ve learned a lot from what reviewers (and interviewers) have said about my writing. They’ve often made me aware of things I’ve been doing without consciously realizing I’ve been doing them. For instance, when I read Graham Good’s review of my first three collections considered together (this appeared in the Southern Humanities Review Vol. 41 no. 4 (2007), pp. 390-94), I thought “Ah, so that’s what I’m trying to do” when he said:

Arthur’s aim in his essays is to move from immediacy to immensity, from the vivid concrete particulars of an incident, an object, or a sight, to the most universal ideas: the human condition, the infinity of space and time, the complexity and connexity of the world.

John Stewart Collis talks about “the extraordinary nature of the ordinary.” Georgia O’Keefe refers to the “faraway nearby.” I like to start with nearby, ordinary things – what lies close to hand and seems commonplace and familiar – and then see the incredible faraway destinations that are led to as soon as you start to think about what’s involved. I’m just amazed at the complexity and depth that’s wired into the everyday things around us. I suppose my essays try to open a window onto that. But it’s not as if I set out to do this. I don’t sit down at my desk and say “Right, it’s time to move from immediacy to immensity,” it’s more something that just happens because of the way I read the world, because of how things fall on the fabric of my consciousness and how I want to write about them as a result.

But when someone like Graham Good comes along and points out what I’m doing, I’m pleased to have what I’m about identified so clearly. (I have, incidentally, been incredibly fortunate in the reviewers who’ve commented on my work. There’s been a real generosity of spirit evident alongside the many perceptive comments they’ve made.)

Just before leaving the movement between small and large, let me make a couple of book recommendations that I think should be on any essayist’s reading list: Henry Petroski’s The Pencil (1989), and Jan Zalasiewicz’s The Planet in a Pebble (2010). These are both wonderful examples of how, starting with something that’s seemingly completely ordinary, you can reach all kinds of unexpected destinations. Both of these books exemplify what Alexander Smith called “the infinite suggestiveness of common things.” That’s something I think essayists need to be alert to. I guess in a sense it’s what they try to transcribe. Smith – whose Dreamthorp: A Book of Essays Written in the Country (1863) is well worth reading for what he says about the genre – also suggested that “the world is everywhere whispering essays and one need only be the world’s amanuensis.” Not infrequently I feel like a kind of harassed scribe attempting to note down the whispered symphonies issuing from the things around me.

You write that essays are like bicycles, “in that they allow us to get close to elusive things.” How does this work in practice for you? Do you sneak up on an idea or does it sneak up on you?

To some extent, I see cars and motorways as emblematic of the objective/academic approach of an article; bicycles and meandering country roads as emblematic of the personal/reflective nature of an essay. This is not to say I always prefer the bicycle – if I want to cover a lot of distance quickly I’d opt for a car. Bicycles are good when you’ve got a shorter journey, when you’ve time to look around and consider things. Just as different vehicles are good for different types of journey, so are different modes of writing. The way an essay unfolds itself wouldn’t fit every occasion. I guess the comparison was in part occasioned because of the way in which cycling allows you to follow all kinds of unnoticed paths and unfrequented byways; how you can easily stop to look at and investigate things, or wheel round and retrace your route to enjoy the view again. If there are roadworks and a red traffic light, you can walk, or cycle on the pavement, instead of waiting in a queue. Cycling seems more in tune with the essay’s individuality than the anonymity of a car. Its pace seems more attuned to the genre’s reflective mood. You can hear things and smell things you’re not aware of when you’re enclosed in a car. But I’m not sure how far the bicycle/essay comparison can be pushed. Maybe I’m particularly susceptible to it because I like to start my writing day by cycling.

As for whether I sneak up on ideas or they sneak up on me, it’s probably a case of my being initially ambushed by an idea and then, when I start to write about it, it’s me who’s trying to hunt down related ideas – though of course it’s not as neat or predictable as this might make it sound. I’m frequently ambushed by ideas that have sneaked up on me as I’m writing. And using “ideas” here maybe gives too intellectual a view of things. My essays often start from things rather than from thoughts, albeit things that are laden with ideas. If you asked me for the ideas that lie at the root of my writing, I’d be hard put to answer (a reviewer like Graham Good would be a better person to ask). But if you asked about the things that spark my writing, that would be easy. Among the objects that have led to essays are: pencils, old photographs, pieces of linen, briefcases, a pelvis bone, the ferrule at the end of a walking stick, some fragments of willow pattern china – all sorts of things.

Adam Gopnik, who guest edited the 2008 edition of that wonderful annual series, The Best American Essays, identifies three types of essay: review essays, memoir essays and what he calls “odd object” essays. This third type, which he claims is “the oldest of all essay forms,” is the kind that “takes a small, specific object, a bit of material minutia….and finds in it a path not just to a large point but also to an entirely different subject.” Many of my essays are indeed concerned with finding paths to unexpected destinations in “material minutia” – we’re back to the large-in-the-small. But, for me, it’s not so much the “odd-object” that needs to be emphasized, more the ordinary object that, once examined, once made the focus for a piece of writing – once essayed – comes to seem odd. Estranging the familiar, helping us see the extraordinary in the everyday, is more what I’m about than offering some kind of peep show into what’s just plain weird.

When you think in terms of things rather than ideas, it’s certainly more a case of objects creeping up on me than my doing so on them – or, since this might seem to bestow an improbable intentionality on what’s inanimate, maybe it would be better to say that it’s more a case of my stumbling across things that have something about them that sparks the desire to write. I don’t go out to look for them in any kind of deliberate, systematic way – they’re all accidental discoveries.

This is Part I of a two-part interview with Chris Arthur, Click here to access Part II.