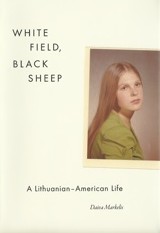

*

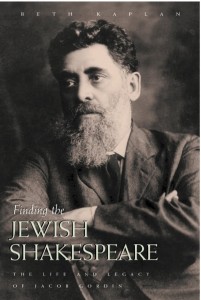

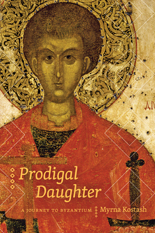

In this revelatory biography, Beth Kaplan sets out to explore the true character and creative achievements of her great-grandfather Jacob Gordin, playwright extraordinaire and icon of the Yiddish stage.

Born of an Anglican mother and a Jewish father who disdained religion, Kaplan knew little of her Judaic roots and less about her famed great-grandfather until beginning her research, more than twenty years ago. Shedding new light on Gordin and his world, Kaplan describes the commune he founded and led in Russia, his meteoric rise among Jewish New York’s literati, the birth of such masterworks as Mirele Efros and The Jewish King Lear, and his seething feud with Abraham Cahan, powerful editor of the Daily Forward. Writing in a graceful and engaging style, she recaptures the Golden Age and colourful actors of Yiddish Theater from 1891 to 1910. Most significantly she discovers the emotional truth about the man himself, a tireless reformer who left a vital legacy to the theater and Jewish life worldwide.

Beth Kaplan is a writer and actress in Canada. She has taught memoir writing at Ryerson University for sixteen years and at the University of Toronto for five. Her essays have appeared in the Globe and Mail and other newspapers and magazines. Visit Beth Kaplan’s website at www.BethKaplan.ca.

Julija Šukys: In your bio in the opening pages of the book, we read that you spent twenty years raising children and writing this book – “they both left home together.” My writing became entangled with and inextricable from my private life once my son was born four years ago. In light of the connection you draw between your kids and the process of writing, I’m interested to know more about the relation between them.

Beth Kaplan: I had my first child in Vancouver when I was nearly 31. I’d been working as an actress in Vancouver for eight years; when I got pregnant, I left the stage and registered to take an MFA in Creative Writing at UBC. So it was as if pregnancy gave me permission to finally sit down and write.

And then the birth of my daughter took that permission away – or at least, made the process difficult. I adored being a mother and didn’t know how to focus on anything else. I’d take the baby to a YMCA daycare for a few hours every few days, so that I could write – but often instead I’d grocery shop or sleep or read the newspaper, things I couldn’t do when she was around. And I felt alone. Almost none of my friends in the theatre or at UBC had kids, and I didn’t know, or even know of, any mother writers.

Someone said once that of the 3 things of vital importance to a married woman – husband, children, work – she could only successfully have two of the three. I thought about Virginia Woolf with husband and work, Margaret Laurence with children and work, L. M. Montgomery with all 3 and a wretched life. There were very few examples of a writer with all 3 successfully. Later I discovered Carol Shields as one very good example, and there are now lots. But around me in the eighties, there were few.

I wrestled with that constantly. I managed to finish the degree long-distance – we moved to Ottawa for my husband’s work in 1983 where I had my son, and then to Toronto in 1985, where I finished my thesis on my great-grandfather and decided to keep going with research and to write a book. When my kids were 6 and 9, my husband and I separated, he moved shortly after that to the States, and so I was a single mother with financial support from him but 100% custody of two difficult children and an old, disintegrating house, in a city where I had no work connections and no family.

The result – the book wasn’t published until 2007. I don’t blame that solely on being a single mother. I also completely lost confidence in myself, was isolated with no support group, had no idea what I was doing – in academic research, there are methods, I just didn’t know what they were. I compared the book to an octopus with its tentacles around my neck – the minute I pried one away, another had me in its grip. And that’s just the writing, let alone getting the thing published. It’s a miracle it ever appeared, in fact.

So this is a very long answer to your question, which is – that I came too late to understand something I call beneficial selfishness. I think writers, artists, have to be selfish sometimes, even with their children. That is, not selfish to the point that their needs are neglected. But selfish in asking them to recognize that their mother has important work that requires something of them. Writing is so invisible. If I were playing the cello or painting, they could hear or see that. But they could see nothing of my work. That was hard for me too, as most of the time, I didn’t believe either, with very little published, that I was a writer.

What helped was writing essays for the CBC and newspapers and for “Facts and Arguments” in the Globe and Mail – I published a lot of short term things that got me out there, got my name in print and showed the world, and me, that I was a writer. Incidentally, many of my essays were about my kids. They grew up being chronicled on the back page of the Globe – always with veto power, of course. But they liked it.

25 years later, I’m still in the same house; the kids live on the other side of town and their rooms here are rented out to help pay the mortgage. I teach but have lots of time, lots of quiet for writing, which is heaven. Except that my daughter has just told me she’s pregnant. Omigod, I’m going to be a grandmother. I can’t wait. But this time, I’ll be able to cuddle and hug and read stories, and then give the baby back and get on with my work.

The fact is that unless you have a spouse who can take over, which I did not, young kids do and must come first, especially when they’re very young (and again when they’re teens but that’s another story.) But that doesn’t mean shelving the work. It means being creative with finding time, and it means taking it and yourself seriously enough to be selfish, sometimes. Otherwise, the work is constantly last, and the book takes 25 years to emerge.

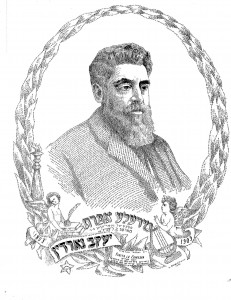

Finding the Jewish Shakespeare constitutes a kind of textual archaeology. It tells the story of your great-grandfather, Jacob Gordin, a Yiddish playwright once compared to Shakespeare and Ibsen, now largely relegated to oblivion. Tell me about the impetus to embark on such a journey, and the research path down which it took you.

I needed to choose a thesis subject for my MFA, and it was my husband who said, You have a great man in your family, write about him. Once he’d said it, of course, I knew that was exactly what I wanted to do. Because there was the mystery I’d grown up with – why did my father and other relatives have such disdain for a man who’d been in his time so revered? So I blithely began, without realizing that almost all my research materials were in New York City– this was 1982, the Dark Ages before Google, so research meant writing letters, making phone calls, and getting on airplanes. The first time I flew from Vancouver to New York for research in 1983, the thrill of arriving at the YIVO Center for Jewish Research on 5th Avenue, asking for their materials about Gordin, and watching the cart rumble up to my desk with all those file boxes. Then opening them eagerly, and finding that nearly everything was in Yiddish or in archaic Russian – the next tiny hurdle, as I spoke and read neither.

I was lucky enough to find a woman who translated from the Yiddish for me for 25 years. So it’s really our book, Sarah Torchinsky’s and mine.

I wrote lots of letters of enquiry, discovered family members to interview – several of them just in time, as they were extremely old already when I found them – and read everything I could find on or around the subject. I didn’t start using a computer for writing until 1987 or so. And Google, of course, much after that. It seems unbelievable now, how much time research took. And several people have pointed out that in the Internet age, we lose the thrill of hunting and holding the actual artifacts and books.

As I read your book, I found myself continually pondering questions of language. Interestingly, Jacob Gordin’s strongest language, and the language he appears to have loved best, was Russian. Yet, he wrote his plays in Yiddish, a language that always represented a bit of a struggle to him. It’s not the language he used in private: with his wife he spoke Russian, and to his children, English (a language it appears he never mastered). Why, once he had gained some success, do you believe that Gordin never made the switch to Russian? Why did he continue to write in Yiddish, despite the limited audiences, the community politics that you describe, and despite the fact that it was not the language in which he planned his plays?

Gordin didn’t switch to Russian because nobody on the Lower East Side ever wanted to hear Russian again; he would have had no audience at all. Yiddish was the language of mothers, of home, hence not only of the theatres but of the burgeoning Yiddish newspapers. Russian was the tongue of the oppressor, the Cossack enemy, there was no place for it amongst the Jews in America. But Gordin always dreamed of going back to Russia one day. Before he died, he knew that his plays were touring Russia – one of his sisters, who still lived there, wrote to him from her town in Ukraine of her pride in going to the theatre to see two of her brother’s plays. But she saw them in Yiddish, not in Russian. There were Yiddish theatres and troupes performing Gordin’s plays in South America and in Eastern Europe – in fact, all over the world.

This is Part I of a two-part interview. Click here to read Part II.

[Images: Courtesy of Beth Kaplan]