*

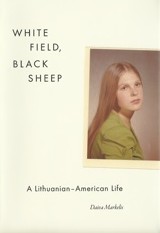

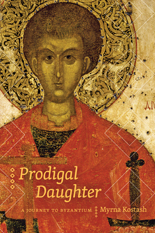

Born and raised in Edmonton, Alberta, Myrna Kostash is a fulltime writer, author of All of Baba’s Children (1978); Long Way From Home: The Story of the Sixties Generation in Canada (1980); No Kidding: Inside the World of Teenage Girls (1987); Bloodlines: A Journey Into Eastern Europe (1993); The Doomed Bridegroom: A Memoir (1997); The Next Canada: Looking for the Future Nation (2000); Reading the River: A Traveller’s Companion to the North Saskatchewan River (2005); The Frog Lake Reader (2009); and most recently, Prodigal Daughter: A Journey into Byzantium (2010).

In 2008 the Writers’ Guild of Alberta presented Kostash with the Golden Pen Award for lifetime achievement. In 2009 she was inducted into the City of Edmonton’s Cultural Hall of Fame, and in 2010, the Writers’ Trust of Canada awarded her the Matt Cohen Award for a Life of Writing.

Prodigal Daughter

A deep-seated questioning of her inherited religion resurfaces when Myrna Kostash chances upon the icon of St. Demetrius of Thessalonica. A historical, cultural and spiritual odyssey that begins in Edmonton, ranges around the Balkans, and plunges into a renewed vision of Byzantium in search of the Great Saint of the East delivers the author to an unexpected place—the threshold of her childhood church. An epic work of travel memoir, Prodigal Daughter sings with immediacy and depth, rewarding readers with a profound sense of an adventure they have lived.

Prodigal Daughter has been awarded the 2011 City of Edmonton Book Prize and the 2011 Writers Guild of Alberta Wilfred Eggleston Prize for Nonfiction.

*

Julija Šukys: Like all good texts of creative nonfiction, Prodigal Daughter is a hybrid text. It’s part travelogue, part historical exploration, and partly a narrative of a personal and spiritual journey. The unifying thread and the organizing metaphor (if that’s not wrong way to think about him) is Saint Demetrius. He’s a complex figure who is appropriated and venerated by a number of cultures and historical narratives. Can you talk a little bit about how Saint Demetrius came to be at the centre of this book for you?

Myrna Kostash: There are 2 versions of this “origin” narrative: the one in the book and the one that is the more truthful story, which out of discretion I have not used. But the published version is close enough: in search of an entry point into a book about Byzantium that I had wanted for years to write, I came across the figure of a saint venerated in the Orthodox Church whose story as told by the Church was exactly the perfect “hook” for me. St Demetrius, according to the hagiography, was martyred in the northern Greek city, Thessalonica, in 304, for the crime of professing faith in Jesus Christ. A couple of centuries later, however, he reappeared in the form of a saint working various miracles in defense of his beloved city, Thessalonica, which was under sustained attack and siege by barbarian marauders. Historically, these barbarians were Avars and Slavs from beyond the Danube, and they never did succeed in taking the city, although they settled in the region, Macedonia. It was this coherence of Slavic ethnicity and the Orthodox spirituality of Byzantium (I was baptised into the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of Canada as an infant) that inspired me to begin this book’s journey: I had a subject.

What did Saint Demetrius stand for when you began the journey of Prodigal Daughter, and what does he stand for now that you’ve come to the end of this particular chapter of writing and life?

For the first three or four years of the project (it did take ten!), I was obsessed by the ethnic implications of “my” saint, namely that a Greek saint, who performed miracles to defend his people, eventually also became a saint venerated by his enemies, the Slavs, my people, when they became Christians. But, as the book discloses, there were a number of turning points in my journey with Demetrius that complicated this simple ethnic formula, points which rerouted my journey, first into an enfolding within the Byzantine world in the Balkans and Constantinople, and second within the Church herself. Having written the book, I am now a faithful member once again of the church of my childhood, and the travelling icon of St Demetrius still goes with me where I go. What he “stands for” is of neither an ethnic nor historical nor even cultural significance but for what all saints stand for in Orthodoxy: an ideal representation of a human being “who is what he ought to be.”

In part, this book is about your somewhat reluctant return to your childhood roots in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. You’re a feminist, a leftist, and a humanist. All this makes for a fraught relationship with your childhood church, so you naturally moved away from it as a young adult. After what you describe as a number of failures of the core ideologies of your youth (the Left, student radicalism, even feminism), you recently found yourself yearning for something else: new meaning and a sense of the sacred.

Can you talk about this path back to Orthodoxy? How did your journey across greater Macedonia and the history of Byzantium help repave an old path differently for you?

I certainly had no spiritual intention for this journey. As with all my previous books, I was initially motivated by intense curiosity about history, and, in the case of Prodigal Daughter, by all the narratives – stories – that have been told about Byzantium, the Balkans and Eastern Christianity, all of which form a kind of cultural grammar for me (and which for most other people, I imagine, represent a triple whammy of exoticism if not downright weirdness). But even so I admit that on previous travels through the region I was always drawn to Orthodox churches as spaces of genuine repose and reflection. Even socialist feminists need that! Perhaps it was just the familiarity of them that drew me in; I certainly wasn’t very interested at that point in the content as opposed to the form of the life of worship they embodied.

But, when it came time to write the book, I realized that, if I were to understand the Byzantine world in which St Demetrius came to be venerated, I had better reacquaint myself with the closest representation of that world in our own time, namely the Orthodox Church. I was living in Saskatoon at the time, as writer-in-residence at the public library, and so I decided to go to a Ukrainian Orthodox church there, to Sunday services on a regular basis. There was much I had forgotten about the forms of worship and much that I never had known or understood (in my childhood in the 1950s the services were entirely in Ukrainian, a language I barely spoke), so I began to read seriously about the history and theology of the Church. For the first time in my life, I read the New Testament, in the form of the Orthodox Study Bible, had a host of questions about what I was reading, and sought the conversation and counsel of a Ukrainian Catholic, Byzantine rite, priest and theologian at the University. He was absolutely brilliant – a deeply consoling mixture of intellectual erudition and spiritual intuition – through whom I became aware of and was prepared to acknowledge something which I mention only glancingly in my book, a deep yearning for the Divine.

Of course, this journey back into Christianity would not have succeeded had I not been convinced, and remain convinced, that there is no contradiction between the core and enduring values of (socialist feminist) humanism and those of the basic Christian teachings. The elaborate mysticism of Orthodox theology is something else, however. I’m still on that journey.

One of the purposes of this book, it seems to me, is to shed light on an ignored and forgotten era: the 1000-year history of Byzantium. Prodigal Daughter is an attempt to engage seriously with the Balkans, a place that still today is so often dismissed as backward, laughable and even murderous. What was the impetus to fix your attention on that time and place?

When I was travelling around eastern and south-eastern Europe in the 1980s and early 1990s (for my books Bloodlines and The Doomed Bridegroom), I became aware of a persistent mythology about “where Europe ends.” Wherever I was – Athens, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Prague, Cracow, Warsaw – people locally insisted that where they were was precisely where Europe “ends.” Which is to say that, where it ends, “Asia” begins. “Asia” signified Turkey in some cases but mostly it signified the Europe that was Orthodox, used the Cyrillic language, had been included in the Ottoman or Czarist Empires, had fallen within the Soviet bloc of countries, had been inflamed by “ancient communal hatreds” well into the 20th century, or some combination of these.

What struck me most was that, first, my relatives who still live in Ukraine were thus “outside” Europe, apparently, and, second, that a large part of the territory “outside” Europe had fallen historically within the borders of Byzantium or been contiguous with it. I was incensed. How was it possible that such disdain and ignorance could be expressed about a thousand-year Empire of astonishing political, cultural and spiritual achievement? (By the way, Byzantines never called themselves such – the term was first applied by a Renaissance German scholar – but named themselves Romans right to the end, as successors to the Late Roman Empire. The city of Rome “fell” in 476 to a Germanic army but the Roman Empire just kept on going, from its new capital of Constantinople, until its defeat in 1453 to the Ottomans.) So began my project to bring into view through a work of literary nonfiction at least some aspects of this world of European otherness.

It’s interesting (actually, maddening) that the first publisher I approached with a proposal to write under the working title Demetrius: Seduction by a Saint, turned it down on the grounds that “we’ve never heard of St Demetrius and we don’t care; write about St Francis.” Of course this did force me to think about how I would make anyone care about St Demetrius – by making the reader care about the narrator, that is me, as it turned out – but I admit that if I read about one more narrative of a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostello, I’m going to scream.

This is Part one of a two-part interview. Click here to read Part II.

[Photo: www.myrnakostash.com]