Mary Gordon, The Shadow Man: A Daughter’s Search for her Father (Bloomsbury, 1997 [1996]).

I read this book on the recommendation of a colleague who thought it could be useful to my work. She was right: I found that it spoke to me on many levels.

I hadn’t expected to have so much in common with Mary Gordon.

Gordon’s book tells the story of her attempt to reconstruct her father’s life and identity through visits to archives and libraries, by wading through murky memories, and taking by both real and imaginary voyages.

She tells us that she connected to her father first and foremost through writing, and that she had become a writer because of him. But her daughterly love and pride get disturbed when she begins to learn unanticipated truths: that her father was both a Lithuanian Jew (who converted to Catholicism) and an anti-Semite, not an American-born, Harvard-educated once-married Catholic, as she had been told. Though he had indeed been a writer, his texts reveal he was not a very good one. His life revealed that he was not a very good husband. Certainly not a very good Jew.

This is a very honest book, so much so that at times it made me uncomfortable. As I read one bald truth after another, I wondered where Gordon got the courage to reveal so much about the things her father believed, about the lies he told, about family secrets. I wondered whom this book was for and who would care.

But just as I asked the question, I began to care about this family. This moment coincided with the author’s offering up of a portrait of her mother: a woman crippled by polio in childhood and struck by senility late in life Gordon’s discussions of her mother’s body struck me as particularly poignant:

For many years, the only adult female body I saw unclothed was, it must be said, grotesque, lopsided, with one dwarf leg and foot and a belly with a huge scar, biting into and discoloring unfirm flesh. She’d point to it and say, “This is what happened when I had you.” (221)

This mother is a phantom presence throughout the book (a shadow woman of sorts), the third member of the family, overlooked and largely unloved. But with her introduction, the narrative somehow fell into place for me, and the book began to sing, if sadly.

It was then that I started to find all sorts of common threads between my own life and work and Mary Gordon’s. I began thinking about my own Lithuanian father who died too young, about my posthumous discoveries about his life, about my own processes of reconciliation with the dead, my relationship to Catholicism, to the country my parents left behind as children, and — most unexpectedly — about my relationship to my own mother and her poor body, battered by multiple sclerosis.

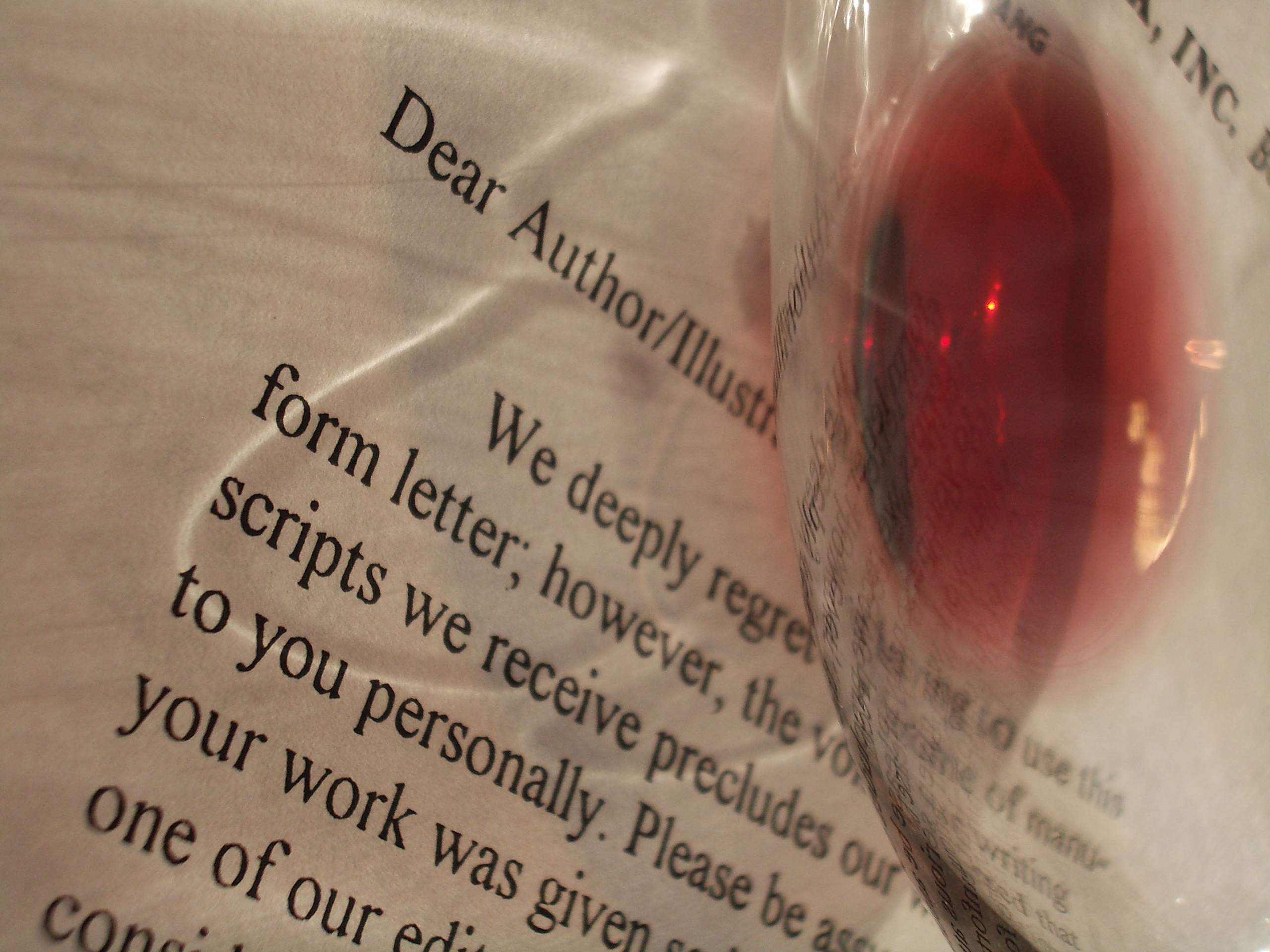

I read this book as I was starting to map out the first chapters of my current project, a family history of sorts. Gordon’s baldness forced me to ask: How much do I dare to tell? How much do I have the right to reveal? What do my parents’ stories have to do with the story of my grandmother that I’m writing?

Mary Gordon’s book is, at least in part, about learning to love someone with all their faults. It’s about forgiveness and acceptance, but without being too pretty or tidy. And (something that surprised me), it managed to speak to me on a most fundamental level by reflecting back my own story of intimacy, familiarity, and discomfort.

[Photo: Thomas Hawk]