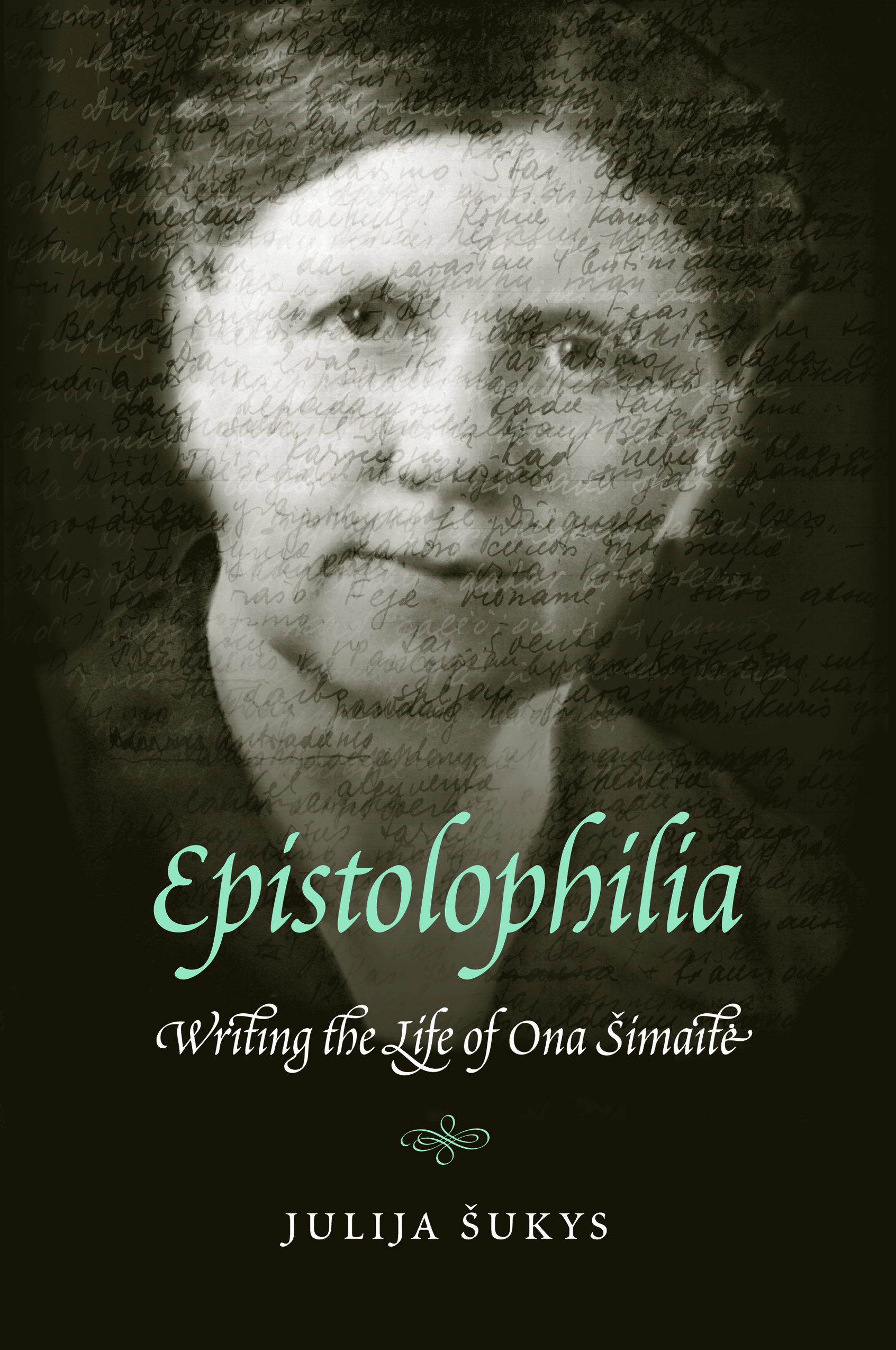

Today I received the last photograph for my forthcoming book, Epistolophilia.

It shows the translator, Vytautas Kauneckas, at the desk in his Lithuanian summer home. Behind him stands a stack of texts sent to him from France by Ona Šimaitė, the subject of my book.

The photograph is from 1959 and has a few water stains. Yet somehow, despite the fact that his image was captured more than fifty years ago in the USSR, the man in the photograph looks utterly contemporary. When I opened the email attachment my colleague at the Vilnius University archives sent me, I found myself deeply moved.

Since I’ve been reading Kauneckas’s letters for the past decade, he (like Šimaitė) is someone I feel I know. Of course, since he died long before I began this project, I never met him. Our posthumous acquaintance only goes one way, but the eyes in that photo tell me I would have liked him not only on paper, but in person too.

In all, my book will contain twenty-seven photographs and two maps. There are lots of images of the book’s subject, the Holocaust rescuer and librarian, Ona Šimaitė, portraits of her correspondents (like Kauneckas), images of her letters and details from her diaries, as well as the shots of significant landmarks I took in the course of my research: her apartments in Paris and Vilnius, and the camps where she was interned.

The process of finding the archival photographs and obtaining permission to publish them has been complex. It’s required a lot of good will and patience on the part of archivists, who (lucky for me) tend to be kind and generous people. I have to say that it’s been worth the trouble, and I can’t wait to see all the visual materials in print.

I wish I could post the Kauneckas photo here, but I must respect the usage agreement I’ve made with the archive — which doesn’t include posting the image on a blog!

I hope that once they appear in Epistolophilia, these photographs will seduce my readers as much as they have me. And that you too will come to love these marginal, ghostly and paper friends as much as I have.