A while ago, I posted a call for volunteers to step forward to help me with a literary experiment. I described a letter I received that invited me to become a member of an informal book club. It went on to outline a kind of literary pyramid scheme, whereby I would send out one book and six letters. In return, I could expect to receive a maximum of 36 previously read books selected by strangers from their very own shelves.

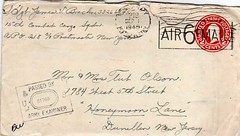

Well, my first book arrived! The package came with a Maryland postmark and inside I found a second-hand copy of Jeffrey Shaara’s Gods and Generals.

Lately, my husband and I have been talking about the benefits of e-books as compared to paper ones. One of the things that the arrival of Gods and Generals has reminded me of is that paper books come with traces of their former lives and readers. And Book #1 contains some interesting clues as to its history.

Trace number one: the former owner’s name (female, interestingly) on the first page.

Trace number two: the book sent contains a business card from the South Mountain State Battlefield in Middletown, Maryland that was likely used as a bookmark. A vestige of some kind of civil war pilgrimage? Did the reader/owner of this book take it on a trip to places it describes?

Trace number three: amazingly, this book has been signed by its author — the autograph is dated Sept. 1, 2002. Why, I wonder, would a reader send away an author-inscribed book to a complete stranger?

All of this reminds me of a 1990s Algerian raï song sung from the perspective of a beauty parlor chair that tells about all the beautiful women and behinds that have graced it. Or of François Girard‘s film The Red Violin that traces the life of an instrument as it is passed from hand to hand. Tracking the life of an object, it turns out, is another way of writing life.

Finally, though American Civil War history is far from a major interest of mine, I’m so thankful for this gift, whose conception is a beautiful gesture of love. Jeffrey Shaara wrote this book as a prequel to his father’s Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Killer Angels, that told the story of the Battle of Gettysburg. He wrote it after his father’s death, so the very text is a kind of conversation with the dead, an elegy, or maybe even a love letter.

Already new avenues for thinking about reading, writing and exchange have opened up for me with this first arrival. I hope more books will come, and with them fodder for a solid essay. If not — if months go by without another book — that will be something to write about too.

Keep reading. Keep writing. Happy Holidays!

[Photo: J Jakobson]