I started my blog almost two years ago after attending a writers’ workshop on publishing in the digital age. There wasn’t much talk of e-books or self-publishing from the presenters. Instead, they hammered a single message into us all day: you, as writers, need an electronic presence . . . preferably a blog. It’s how you control the message of who you are and what you do. Your site is Google’s gateway to you and your work.

Like many writers, I long resisted self-promotion, finding the very idea distasteful and embarrassing. But I’d learned from the experience of publishing my first (mostly overlooked) book, Silence is Death (oh! the irony of that title in this context…), that if you don’t advocate for your own work, no one will. I knew that this time around, I had to swallow pride and do things differently. So, in preparation for the publication of my second book, Epistolophilia, I decided to take the workshop’s advice. I bought a domain name (my own name as well as my books’ titles), and started a blog.

Despite my initial reticence, blogging quickly brought unexpected rewards. From the very beginning, I enjoyed the discipline regular posting required, and the way the site grew slowly, like a garden or a manuscript. I’m obsessed with archives, so I love the way blogs are keepers of their own histories. Finally, I have been delighted by the community-building opportunities that a blog creates.

A long time ago, I sat on an academic board that organized a biannual conference whose participants’ median age was going up and up. Board members worried constantly about the organization’s impending death and wondered how to attract younger attendees. “Offer them something,” I suggested. “An opportunity to win a book prize or a shot at a fellowship. Offer them something, and they will come.” So, that’s what we did. Once the association started a modest fellowship program and book prize, youthful scholars began returning to the association (and the financial investment quickly paid for itself).

The same principle works for a blog: offer something, and readers will come.

Blogs need not be navel-gazing, self-aggrandizing, or mean-spirited. When setting up the parameters of my blog, I asked myself how I could serve fellow writers. I decided on a ratio of 1:2. For every post about myself or my work, I featured at least 2 items about someone or something else: a review of a book or essay; a funding announcement or call for submissions; an author interview with a fellow writer of creative nonfiction.

By shining the spotlight (small as mine may be) on another writer, or by giving her a platform to talk about her work, I not only gain traffic on the blog (for every other writer brings friends and fans with her), I also gain insight, contacts, friends, knowledge and the occasional free book.

The more I extend myself to other writers, the more they reach back.

Writers are also readers. We are each other’s colleagues, but also each other’s audiences. Serving writers means reaching readers.

Be brave, be bold, and build. Then open yourself up to others and share.

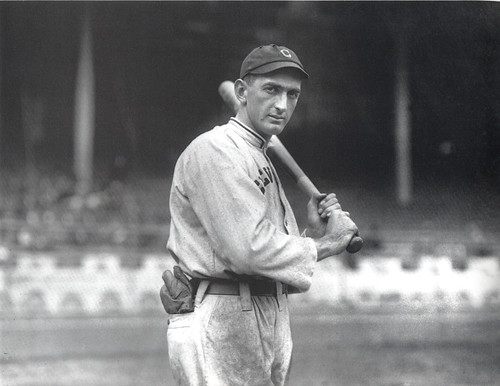

[Photo: Shoeless Joe Jackson, by John McNab]

This post is part of a weekly series called “Countdown to Publication” on SheWrites.com, the premier social network for women writers.