Last summer, I spent a few weeks in the State Historical Society of Missouri developing an assignment for a new course called Women Writing Lives. I envisioned brining students into the archives and wanted them to get a sense of how enthralling archival work could be. It was more successful than I ever could have predicted, so I wrote a short piece about it for Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. Here it is.

CNF Conversations: An Interview with Mary Cappello

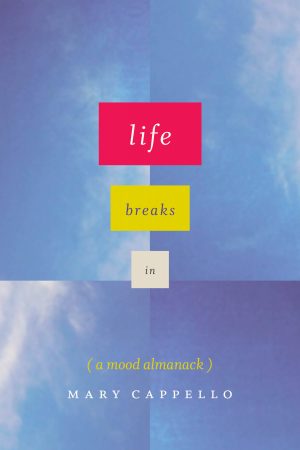

Mary Cappello, Life Breaks In (A Mood Almanack). University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Mary Cappello is the author of five books of literary nonfiction, including Awkward: A Detour (a Los Angeles Times bestseller); Swallow, based on the Chevalier Jackson Foreign Body Collection in Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum; and, most recently, Life Breaks In: A Mood Almanack. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, Salon.com, The Huffington Post, on NPR, in guest author blogs for Powells Books, and on six separate occasions as Notable Essay of the Year in Best American Essays. A Guggenheim and Berlin Prize Fellow, a recipient of The Bechtel Prize for Educating the Imagination, and the Dorothea Lange-Paul Taylor Prize, Cappello is a former Fulbright Lecturer at the Gorky Literary Institute (Moscow), and currently Professor of English and creative writing at the University of Rhode Island.

About Life Breaks In: Some books start at point A, take you by the hand, and carefully walk you to point B, and on and on.

This is not one of those books. This book is about mood, and how it works in and with us as complicated, imperfectly self-knowing beings existing in a world that impinges and infringes on us, but also regularly suffuses us with beauty and joy and wonder. You don’t write that book as a linear progression — you write it as a living, breathing, richly associative, and, crucially, active, investigation. Or at least you do if you’re as smart and inventive as Mary Cappello.

What is a mood? How do we think about and understand and describe moods and their endless shadings? What do they do to and for us, and how can we actively generate or alter them? These are all questions Cappello takes up as she explores mood in all its manifestations: we travel with her from the childhood tables of “arts and crafts” to mood rooms and reading rooms, forgotten natural history museums and 3-D View-Master fairytale tableaux; from the shifting palette of clouds and weather to the music that defines us and the voices that carry us. The result is a book as brilliantly unclassifiable as mood itself, blue and green and bright and beautiful, funny and sympathetic, as powerfully investigative as it is richly contemplative.

“I’m one of those people who mistrusts a really good mood,” Cappello writes early on. If that made you nod in recognition, well, maybe you’re one of Mary Cappello’s people; you owe it to yourself to crack Life Breaks In and see for sure.

“Are we sometimes not astonished by the beautiful futility of encountering some sudden fugitive moment that renders us so vulnerable to ‘unanticipated forms’: of perhaps an inner light or an inner dark? Here, with Mary Cappello’s ravishing prose, lies a vibrating scalpel that intricately parts the belly of little swirling vertigos that we have no name for but know so deeply.”

— The Brothers Quay

“Mood is alpha and omega, it is everything and nothing” – Mary Cappello, Life Breaks In

Julija Šukys: Mary, first of all, congratulations on your book. Life Breaks In is learned, rigorous, and, at times, intimate and devastating. On the one hand, the text is incredibly wide-ranging: you take the reader through subjects as varied as Joni Mitchell’s music, mood rings, your father’s darkness, your friend’s death from cancer, taxidermy, and the weird queer history of children’s books. But on the other hand, your book is impressively focused and disciplined as it continually loops back to thinking about mood as sound, as space, as reading, as color. It does so in an almost oblique way and manages to look closely at something that is otherwise almost invisible.

You have written that the challenge of the book was “not to chase mood, track it, or pin it down: neither to explain nor define mood – but to notice it – often enough, to listen for it – and do something like it without killing it in the process” (15). It seems like mood is something that you can only see through the prism of something else, like those ghosts in children’s cartoons that become visible in the dust beaten out of a chalkboard brush. Can you say a little bit about how you came to your subject? And can you talk a bit about the title, Life Breaks In, and the role that rupture plays in a meditation on mood?

Mary Cappello: This question of how we come to our subjects is perpetually intriguing to me. Some subjects for me have been urgent givens (for example, cancer); others, I’ve arrived at through intricately circuitous routes even though, once there, they greeted me with a kind of “ah-ha” or “but-of-course” feeling (e.g., awkwardness); still others were the result of an accidental encounter, what Barthes might call a “lucky find,” almost like a punctum in photography (e.g., the Chevalier Jackson foreign body collection). Mood happened for me in yet another way—in its own way—and it was as though it was always hovering. The subject has played around the edges of my consciousness for many years, and, by the time I brought the book to completion, it felt as though it was the work toward which all of my work had been tending.

Sometimes I’ll be reading a book I’ve read a thousand times, and I’ll find marginalia that I wrote in it dating back twenty years relative to mood. I guess I’m trying to say that mood felt to me like the thing I’ve been writing about all along but that had never announced itself as such—which makes me wonder if this is a sort of experience relevant to all writers. Unlike my other ostensible “subjects,” mood seemed to be following me rather than vice versa.

The title is a phrase lent to me by Virginia Woolf who wrote these wonderfully suggestive lines in one of her diary entries: “How it would interest me if this diary were ever to become a real diary: something in which I could see changes, trace moods developing; but then I should have to speak of the soul, & did I not banish the soul when I began? What happens is, as usual, that I’m going to write about the soul, & life breaks in.”

I’m really interested in the time/space that mood exists in—I mean, moods seem to be a bedrock of our being (we’re never not in a mood of one sort or another), at the same time that moods seem to exist quite apart from our ability to perceive them. Are moods co-terminus with the thing we call “life” or “living”? Does life interrupt mood or do moods interrupt life? This is related to the aesthetic problem that you refer to in your question—I mean, here’s this thing that is ephemeral, amorphous but ever-present and foundational. It will not let you pin it down, and it might only come into view when you aren’t trying to discover it. If you look too directly at it, it may not show itself, or will vanish. And the minute it does materialize, life is sure to break in, and poof, it’s gone.

I hope that readers take pleasure in the unexpected ways in which breaks enter in to the book, and I’d hardly exhaust those ways if I mentioned just a few, like day break and breaks in clouds; breakthroughs and heartbreaks; the breaking of a silence and the breaking into song.

As you know, I read this book very slowly, in fits and starts. At first, my pace embarrassed me (confession: I’m a slow reader at the best of times), but the deeper into the book I got and the more I thought about what you were doing in it, the more I made peace with my meandering methods.

You’ve subtitled the book “A Mood Almanack” and elucidate it like this: “the almanack is a revelatory book and a book of secrets. A book whose tidings we look out for and consult from time to time…. A book to wander in a desert with…. A book whose only requirement is that we float into and out from the streets where we live, pausing long enough to feel the mood beneath us shift.” (16) It occurs to me now that this is a book that values the slow reveal and invites a reader to go off, wander around, and return according to her inclinations (or, indeed, mood).

Can you say a little more about your notion of the book as almanack? (By the way, my autocorrect keeps trying to remove the k at the end of that word!)

All that I can say about the slow reveal is: yes, yes, yes. Meandering methods, both in writing and in reading, yes. I’m so glad that this is how you experienced the book, Julija. I seem to have found my ideal reader!

Mood called for what I describe as “cloud-writing,” which asked for an aesthetic of hover and drift. Like my second book, Awkward: A Detour, this book can be dipped into, read front to back, or not. For the reader interested in moving front to back, the book is structured to allow for various more and more voluble returns (as you note in your opening lines here), and a frame tale relative to voice and mood (most especially, the role of the voices of our earliest caretakers, how we may have come to receive those voices and, if we grew up to be writers, how we later constructed voice-imbued atmospheres in the form of writing).

I had a lot of reasons for calling the book an “almanack,” and with that older spelling, too. I wanted to nod in the direction of those early autobiographical experiments of Ben Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack, but also the less well-known book by Djuna Barnes, her Ladies Almanack (1928) and its wonderful sub-title, “showing their Signs and their Tides; their Moons and their Changes; the Seasons as it is with them; their Eclipses and Equinoxes; as well as a full Record of diurnal and nocturnal Distempers, written & illustrated by a lady of fashion.”

Formally, though, the “almanack” appealed to me for its generic specificity and range: an almanack (especially a “farmer’s alamanack”) shares a kinship with mood-writing because it’s a place we turn to for chartings of weather patterns and cloud movements, the prospect of a good harvest or a drought, and it’s a space where different types of knowledge on a subject can intermingle, where folk wisdom meets philosophy, aphorism and recipes coincide—more to the point, where a kind of non-knowledge or useless knowledge (à la Gertrude Stein) prevails. I didn’t structure the book like an almanack—this would have felt artificial to me—but when I learned more about the etymology of the word, I couldn’t believe how fitting it was for a mood-book: from classical Arabic, munaāk, it refers to a place where a camel kneels, a station on a journey or the halt at the end of a day’s travel. Simultaneously, it derives from cognate Arabic words for “calendar,” and “climate.” This blew my mind because it seemed to bring together so many mood-relatives: temporality, charts and unchartability, atmosphere, rest and pause. There is also a warmth to the Farmer’s Almanack that I was hoping to invoke.

Continue reading “CNF Conversations: An Interview with Mary Cappello”

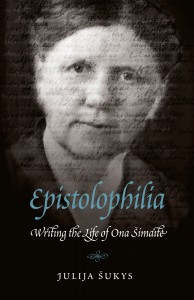

Maisonneuve Magazine Names Epistolophilia One of the Best Books of 2012

Maisonneuve Magazine is published out of Montreal and “has been described as a new New Yorker for a younger generation, or as Harper’s meets Vice, or as Vanity Fair without the vanity.” The quarterly offers “a diverse range of commentary across the arts, sciences, daily and social life.”

When the publication asked its contributors to share their favourite reads of the year, Crystal Chan chose Epistolophilia by yours truly. Here’s what she says about it:

My favourite line is the last one. To be considered as working in the tradition of Virginia Woolf — what a gift.

Happy Holidays, Merry Christmas, Bonnes Fêtes, su šventėm!

May the coming year bring you peace, good health, and good writing.

[Photo: 2day929]

Author Interview in Foreword Reviews this Week

Here’s an interview I did with ForeWord Reviews, a great publication that focuses on books published by independent presses. You can access the original here (scroll down to the bottom of the page):

Conversational interviews with great writers who have earned a review in ForeWord Reviews. Our editorial mission is to continuously increase attention to the versatile achievements of independent publishers and their authors for our readership.

Julija Šukys

Photo by Genevieve Goyette

This week we feature Julija Šukys, author of Epistolophilia.

978-0-8032-3632-5 / University of Nebraska Press / Biography / Softcover / $24.95 / 240pp

When did you start reading as a child?

I learned to read in Lithuanian Saturday school (Lithuanian was the language my family spoke at home). I must have been around five when, during a long car trip from Toronto to Ottawa to visit my maternal grandparents, I started deciphering billboards. By the time we’d arrived in Ottawa, I’d figured out how to transfer the skills I’d learned in one language to another, and could read my brother’s English-language books.

What were your favorite books when you were a child?

E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web and Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory come immediately to mind. These are books that I read and reread.

What have you been reading, and what are you reading now?

I recently finished Mira Bartok’s memoir The Memory Palace, which I found really extraordinary. I’m now reading Nicholas Rinaldi’s novel The Jukebox Queen of Malta, which was recommended by the writer Louise DeSalvo. My husband, son, and I are nearing the end of an eight-month sabbatical on the island of Gozo, Malta’s sister island, so I’m trying to learn more about this weird and wonderful place before we head home to Montreal.

Who are your top five authors?

WG Sebald: To me, his books are a model of the possibilities of nonfiction. They’re smart, poetic, restrained, and melancholy.

Virginia Woolf: I (re)discovered her late in life, soon after the birth of my son, when I was really struggling to find a way back to my writing. She spoke to me in ways I hadn’t anticipated.

Marcel Proust: I read In Search of Lost Time as a graduate student, and the experience marked me profoundly. This is a book that doesn’t simply examine memory, but enacts and leads its reader through a process of forgetting and remembering.

Assia Djebar: I wrote my doctoral dissertation, in part, on Assia Djebar, an Algerian author who writes in French. Her writing about women warriors, invisible women, and the internal lives of women has strongly influenced me. Djebar, in a sense, gave me permission to do the kind of work I do now, writing unknown female life stories.

Louise DeSalvo: I discovered De Salvo’s work after the birth of my son when I was looking for models of women who were both mothers and writers. DeSalvo is a memoirist who mines her life relentlessly and seemingly fearlessly. She’s a model not only in her writing, but in the way she mentors and engages with other writers.

What book changed your life?

There are two. Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and her collection Women and Writing, especially the essay “Professions for Women.” I read these at the age of thirty-six when my son was approaching his second birthday. My work on Epistolophilia had stalled, and I was exhausted. I was trying to create conditions that would make writing possible again, but I was struggling with some of the messages the outside world was sending me (that, for example, it was selfish of me to put my son in daycare so that I could write; or now that I’d had a baby, my life as a woman had finally begun, and I could stop pretending to be a writer).

I remember feeling stunned by how relevant Woolf’s words remained more than eighty years after she’d written them. What changed my life was her prescription (in “Professions for Women”) to kill the Angel in the House. Before reading this, I’d already begun the process of killing my own Angel, but Woolf solidified my resolve. There’s no doubt that she is in part responsible for the fact that I finished Epistolophilia and that I continue to write.

Continue reading “Author Interview in Foreword Reviews this Week”

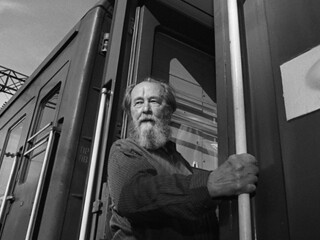

“Let us now praise famous men”: On Breaking Conventions and Women’s Biography

This morning I read a really interesting conversation with Michael Scammel, the biographer of Alexsandr Solzhenitsyn and Arthur Koestler. A lot of what Scammel said about his path to biography resonated with me. He describes having wanted to become a fiction writer in his twenties (just as I did), only to find that he “didn’t have the stamina for it.” The urge to be a biographer crept up on him without his realizing it. And the questions of biography — of how tell a life in an engaging and instructive way — came to him naturally (just as they have to me).

Scammel talks about what a biographer must do: wear learning lightly, entertain as well as instruct, write what is genuinely fact-based, and hone the novelistic skills of setting a scene.

What a biographer must never, ever do, Scammell underlines, is lie. “The oath is against invention,” he stresses, “if you’re not sure of something, you don’t put it in.” The one way around uncertainty is to speculate, but honestly. “You have to confess and say, ‘This is what I think may have occurred, but I can’t prove it.’ And that way you have your cake and eat it too.”

All in all, it’s a great conversation. Reading Scammell’s descriptions of his process, I recognized many of my own struggles writing Epistolophilia, but, I must admit, that something was nagging at me as I read this interview — I couldn’t help wondering: well, what about women?

In the whole conversation, only one female biographer, Janet Malcolm (author of many books, including Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice) is mentioned. And, interestingly, she’s held up as an exception in her approach to biographical writing, since her books “aren’t biographies in the usual sense.”

This is no coincidence. It seems to me that there’s a gender divide in biography.

Women writing about women almost always produce texts that aren’t “biographies in the usual sense.” This is because women’s lives (and here I’m thinking both of female biographical subjects as well as female biographers) are structured differently and have different rhythms and arcs than male lives (or, I suppose, “usual lives”). It’s something I grappled with in a chapter called “Writing a Woman’s Life” in Epistolophilia. Here’s an excerpt:

Why have women traditionally written so little when compared with men? And what needs to change in women’s lives in order to make writing possible? Why have women been so absent from literary history? The answer, Virginia Woolf tells us in A Room of One’s Own, lies in the conditions of women’s lives. Women raise children, have not inherited wealth, and have had had fewer opportunities to make the money that would buy time for writing. Women rarely have partners who cook and clean and carry (or share equally) the burden of home life. Our lives have traditionally been and largely continue to be fractured, shared between child care, kitchen duties, family obligations. To write, what a woman needs most is private space (a room of one’s own), money and connected time (that only money can buy). Woolf wrote her thoughts on women and writing in the 1920s, a time before all the ostensibly labor-saving devices like washing machines, slow cookers, microwave ovens, dishwashers and so on. Most North American women now work outside the home, and most can probably find a corner in their houses to call their own. Problem solved? No. Despite all this, we still find ourselves fractured and split.

Women biographers often enter into the text to dialogue with their subjects, instead of vanishing in the shadow of her creative achievement (which, Scammell’s interviewer Michael McDonald reminds us, used to be the mark of a good biographer). Increasingly, we do not take up Ecclesiasticus’s call, “Let us now praise famous men.” Instead, more and more of us answer the faint call of foremothers to excavate their invisible and unknown lives out of the detritus of the past.

When Scammell explains his reasons for abandoning an initial attempt to insert himself into Koestler’s story, choosing instead to write the biography in the “usual third-person style,” I respect his reasoning. First-person narrative, in his context, may indeed have been distracting and mightn’t have added much value to the text.

In a weird way, I sympathize accutely, because I desperately wanted to write a “straight biography” of my subject, Ona Šimaitė in the “usual third-person style.” It didn’t work.

“The conventions are there for a reason,” says Scammell. Perhaps.

And they work very well for certain tasks, like praising famous men. They don’t, however, work so well for telling the lives of obscure women.

I learned this the hard way.

After reading this interview, I’m left with many questions. Here I am on the eve of publishing a biography of a woman, and I wonder about the gendered aspect of the genre that has chosen me. Will women biographers, feminist biographers, and archaeologists of the feminine past forever be considered exceptions, curiosities, and breakers of convention? How wide must the margins grow before they finally touch the centre? Will women’s biography ever become simply biography “in the usual sense”? And if it did, what would we think?

[Photo: Alexander Solzhenitsyn, by openDemocracy]

This post is part of a weekly series called “Countdown to Publication” on SheWrites.com, the premier social network for women writers.

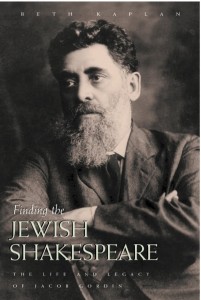

CNF Conversations: An Interview with Beth Kaplan (Part I)

*

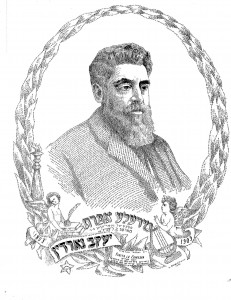

In this revelatory biography, Beth Kaplan sets out to explore the true character and creative achievements of her great-grandfather Jacob Gordin, playwright extraordinaire and icon of the Yiddish stage.

Born of an Anglican mother and a Jewish father who disdained religion, Kaplan knew little of her Judaic roots and less about her famed great-grandfather until beginning her research, more than twenty years ago. Shedding new light on Gordin and his world, Kaplan describes the commune he founded and led in Russia, his meteoric rise among Jewish New York’s literati, the birth of such masterworks as Mirele Efros and The Jewish King Lear, and his seething feud with Abraham Cahan, powerful editor of the Daily Forward. Writing in a graceful and engaging style, she recaptures the Golden Age and colourful actors of Yiddish Theater from 1891 to 1910. Most significantly she discovers the emotional truth about the man himself, a tireless reformer who left a vital legacy to the theater and Jewish life worldwide.

Beth Kaplan is a writer and actress in Canada. She has taught memoir writing at Ryerson University for sixteen years and at the University of Toronto for five. Her essays have appeared in the Globe and Mail and other newspapers and magazines. Visit Beth Kaplan’s website at www.BethKaplan.ca.

Julija Šukys: In your bio in the opening pages of the book, we read that you spent twenty years raising children and writing this book – “they both left home together.” My writing became entangled with and inextricable from my private life once my son was born four years ago. In light of the connection you draw between your kids and the process of writing, I’m interested to know more about the relation between them.

Beth Kaplan: I had my first child in Vancouver when I was nearly 31. I’d been working as an actress in Vancouver for eight years; when I got pregnant, I left the stage and registered to take an MFA in Creative Writing at UBC. So it was as if pregnancy gave me permission to finally sit down and write.

And then the birth of my daughter took that permission away – or at least, made the process difficult. I adored being a mother and didn’t know how to focus on anything else. I’d take the baby to a YMCA daycare for a few hours every few days, so that I could write – but often instead I’d grocery shop or sleep or read the newspaper, things I couldn’t do when she was around. And I felt alone. Almost none of my friends in the theatre or at UBC had kids, and I didn’t know, or even know of, any mother writers.

Someone said once that of the 3 things of vital importance to a married woman – husband, children, work – she could only successfully have two of the three. I thought about Virginia Woolf with husband and work, Margaret Laurence with children and work, L. M. Montgomery with all 3 and a wretched life. There were very few examples of a writer with all 3 successfully. Later I discovered Carol Shields as one very good example, and there are now lots. But around me in the eighties, there were few.

I wrestled with that constantly. I managed to finish the degree long-distance – we moved to Ottawa for my husband’s work in 1983 where I had my son, and then to Toronto in 1985, where I finished my thesis on my great-grandfather and decided to keep going with research and to write a book. When my kids were 6 and 9, my husband and I separated, he moved shortly after that to the States, and so I was a single mother with financial support from him but 100% custody of two difficult children and an old, disintegrating house, in a city where I had no work connections and no family.

The result – the book wasn’t published until 2007. I don’t blame that solely on being a single mother. I also completely lost confidence in myself, was isolated with no support group, had no idea what I was doing – in academic research, there are methods, I just didn’t know what they were. I compared the book to an octopus with its tentacles around my neck – the minute I pried one away, another had me in its grip. And that’s just the writing, let alone getting the thing published. It’s a miracle it ever appeared, in fact.

So this is a very long answer to your question, which is – that I came too late to understand something I call beneficial selfishness. I think writers, artists, have to be selfish sometimes, even with their children. That is, not selfish to the point that their needs are neglected. But selfish in asking them to recognize that their mother has important work that requires something of them. Writing is so invisible. If I were playing the cello or painting, they could hear or see that. But they could see nothing of my work. That was hard for me too, as most of the time, I didn’t believe either, with very little published, that I was a writer.

What helped was writing essays for the CBC and newspapers and for “Facts and Arguments” in the Globe and Mail – I published a lot of short term things that got me out there, got my name in print and showed the world, and me, that I was a writer. Incidentally, many of my essays were about my kids. They grew up being chronicled on the back page of the Globe – always with veto power, of course. But they liked it.

25 years later, I’m still in the same house; the kids live on the other side of town and their rooms here are rented out to help pay the mortgage. I teach but have lots of time, lots of quiet for writing, which is heaven. Except that my daughter has just told me she’s pregnant. Omigod, I’m going to be a grandmother. I can’t wait. But this time, I’ll be able to cuddle and hug and read stories, and then give the baby back and get on with my work.

The fact is that unless you have a spouse who can take over, which I did not, young kids do and must come first, especially when they’re very young (and again when they’re teens but that’s another story.) But that doesn’t mean shelving the work. It means being creative with finding time, and it means taking it and yourself seriously enough to be selfish, sometimes. Otherwise, the work is constantly last, and the book takes 25 years to emerge.

Finding the Jewish Shakespeare constitutes a kind of textual archaeology. It tells the story of your great-grandfather, Jacob Gordin, a Yiddish playwright once compared to Shakespeare and Ibsen, now largely relegated to oblivion. Tell me about the impetus to embark on such a journey, and the research path down which it took you.

I needed to choose a thesis subject for my MFA, and it was my husband who said, You have a great man in your family, write about him. Once he’d said it, of course, I knew that was exactly what I wanted to do. Because there was the mystery I’d grown up with – why did my father and other relatives have such disdain for a man who’d been in his time so revered? So I blithely began, without realizing that almost all my research materials were in New York City– this was 1982, the Dark Ages before Google, so research meant writing letters, making phone calls, and getting on airplanes. The first time I flew from Vancouver to New York for research in 1983, the thrill of arriving at the YIVO Center for Jewish Research on 5th Avenue, asking for their materials about Gordin, and watching the cart rumble up to my desk with all those file boxes. Then opening them eagerly, and finding that nearly everything was in Yiddish or in archaic Russian – the next tiny hurdle, as I spoke and read neither.

I was lucky enough to find a woman who translated from the Yiddish for me for 25 years. So it’s really our book, Sarah Torchinsky’s and mine.

I wrote lots of letters of enquiry, discovered family members to interview – several of them just in time, as they were extremely old already when I found them – and read everything I could find on or around the subject. I didn’t start using a computer for writing until 1987 or so. And Google, of course, much after that. It seems unbelievable now, how much time research took. And several people have pointed out that in the Internet age, we lose the thrill of hunting and holding the actual artifacts and books.

As I read your book, I found myself continually pondering questions of language. Interestingly, Jacob Gordin’s strongest language, and the language he appears to have loved best, was Russian. Yet, he wrote his plays in Yiddish, a language that always represented a bit of a struggle to him. It’s not the language he used in private: with his wife he spoke Russian, and to his children, English (a language it appears he never mastered). Why, once he had gained some success, do you believe that Gordin never made the switch to Russian? Why did he continue to write in Yiddish, despite the limited audiences, the community politics that you describe, and despite the fact that it was not the language in which he planned his plays?

Gordin didn’t switch to Russian because nobody on the Lower East Side ever wanted to hear Russian again; he would have had no audience at all. Yiddish was the language of mothers, of home, hence not only of the theatres but of the burgeoning Yiddish newspapers. Russian was the tongue of the oppressor, the Cossack enemy, there was no place for it amongst the Jews in America. But Gordin always dreamed of going back to Russia one day. Before he died, he knew that his plays were touring Russia – one of his sisters, who still lived there, wrote to him from her town in Ukraine of her pride in going to the theatre to see two of her brother’s plays. But she saw them in Yiddish, not in Russian. There were Yiddish theatres and troupes performing Gordin’s plays in South America and in Eastern Europe – in fact, all over the world.

This is Part I of a two-part interview. Click here to read Part II.

[Images: Courtesy of Beth Kaplan]

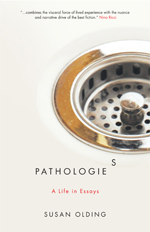

CNF Conversations: An Interview with Susan Olding (Part I)

Susan Olding, Pathologies: A Life in Essays. Calgary: Freehand Books, 2008.

*

Susan Olding’s first book, Pathologies: A Life in Essays, won the Creative Nonfiction Collective’s Readers’ Choice Award, and was nominated for the BC National Award for Canadian Nonfiction. Her essays, fiction, and poetry have appeared widely in Canada and the United States, and she is the recipient of several prizes and awards, including the Edna Award from The New Quarterly, the Brenda Ueland Prize for Literary Nonfiction, and the Prairie Fire Creative Nonfiction Contest. She lives with her family in Kingston, Ontario, where she’s currently working on a novel and a second book of essays.

In these fifteen searingly honest personal essays, Susan Olding takes us on an unforgettable journey into the complex heart of being human. Each essay dissects an aspect of Olding’s life experience—from her vexed relationship with her father to her tricky dealings with her female peers; from her work as a counsellor and teacher to her persistent desire, despite struggles with infertility, to have children of her own. In a suite of essays forming the emotional climax of the book, Olding bravely recounts the adoption of her daughter, Maia, from an orphanage in China, and tells us the story of Maia’s difficult adaptation to the unfamiliar state of being loved.

Written with as much lyricism, detail, and artfulness as the best short stories, the essays in Pathologies provide all the pleasures of fiction combined with the enrichment derived from the careful presentation of fact.

Julija Šukys: Pathologies spans the greater part of your life. We read about your childhood and adolescence, a difficult relationship with your parents, and then the narrative settles into the subjects of mothering and writing. It feels like a life’s work. Is that so?

Susan Olding: It often felt like a life’s work. It took me about a decade to write it! But I hope I have a few more years—and more books—before I die.

I’m not a quick writer, and essays tend to demand steeping time. It’s enormously frustrating at times.

You take the title from your father’s profession. In the epigraph to the book you give two different meanings for the word: one has to do with the study and diagnosis of illness; the other (more surprising) is pathology as the study of passions and emotions. The word “pathology” contains within it the root “logos” (word). I wonder if you could tell me a little bit about the links you see between a love for words, illness, and passion.

My love of words is an infectious passion? Well…I hope it’s infectious, at any rate!

Talk a little about the process of how the book came about.

The idea for the book came in a flash of intuition. I work at the Queen’s University Writing Centre. In one of the tutoring rooms there used to be an old copy of the OED. Waiting for a student to appear for her appointment one day, I opened the dictionary on a whim to the definitions you mention above. The metaphorical possibilities immediately struck me, and the idea for the book was born. I would put my own life and experiences under the microscope, as it were, to discover what might result from that experiment.

I had already written the first two essays. The rest came afterwards. But because it took so long to write, and because the essays are tied to life events, by the end I had included pieces that I literally could not have imagined at the project’s start. I also cast aside some of my initial ideas. So ultimately the process felt quite organic.

I later learned that this is how Montaigne’s work came together. It accreted. When he began his project, he knew only that he would use himself as subject, would question himself, would “roll about” in himself. But he didn’t know what shape his thoughts would take until he was finished writing.

By the end, he had invented a new form. I didn’t invent; I’m his lucky inheritor. But it often felt as if I were inventing, because initially, I didn’t have many contemporary models, especially in Canada. I had read and loved Virginia Woolf’s essays, and Orwell’s, and many other classics of the genre. But I hadn’t thought of them as essays, per se—I was just reading anything and everything by authors that I loved, which is what I tended to do back then.

I’d also read, and loved, the work of some contemporary American practitioners of the form—Richard Rodriguez, Adrienne Rich, Gretel Erlich, Joan Didion, Annie Dillard, Alice Walker. And I’d loved Berger, and Benjamin, and Camus. But when I started to send out my own work, nobody in Canada seemed to be publishing literary essays. Not by unknown writers, at any rate. Since then, there’s been an explosion of creative nonfiction in the literary journals. But in the late 90s, the only place I could think to send my work in Canada was Event, during their annual nonfiction contest. I was lucky enough to be chosen a winner of one of those contests, for the first piece in the book, “Pathology,” and that gave me the encouragement I needed to continue.

There’s an anxiety that I felt traced through the book almost from the very beginning: namely, the right to write. It’s a question that I too struggle with. Indeed, perhaps anyone who writes about real people, especially loved ones, must grapple with a fear of exploitation or overstepping boundaries. At one point you ask if writing lives is “a gift or a lie,” and about the danger of “flattening” characters in nonfiction. I’m interested to know more about these ideas.

In some sense I had to write my way into permission to write. And that was a slow and painstaking process.

One barrier was the fear that writing itself was self-indulgent. Shouldn’t I be doing more important and socially useful things? And writing about myself, which for some peculiar reason I seemed to need to do, seemed even more self-indulgent.

The title of Alice Munro’s Who Do You Think You Are? lodged in my brain. Pathologies is my answer, I guess. Writing it has banished that voice, the one that told me I had no right to write at all.

For I discovered something in the process: it’s impossible to write well about anything, including and perhaps especially about the self, without humility. Anyone who aspires to art writes in the service of the work, not the self. So writing well is the best defence.

As for the second issue—the fear of flattening or misrepresenting or hurting or exploiting others—that arose very early in the project. I remember when I finished the first piece, about my relationship with my dad, I showed it to two friends who happen to be sisters. One is a writer, and one a psychiatrist. The first friend read it and said, “That’s a powerful piece; of course you must publish it.” The second friend read it and said, “That’s a powerful piece; of course you can’t publish it.”

What a perfect illustration of the different attitudes I’ve since encountered, both in others and within myself!

I don’t think it really matters what genre we choose. People have been just as hurt by fictional portrayals as by their appearance in narrative journalism as by their appearance in memoirs and personal essays and poems. So this question should occur to every writer.

And in the end, I don’t think there are any easy answers. We’re social beings. Our lives intersect with others. So if we write, inevitably we include others in what we write, unless we’re hermits, and even then we would probably include remembered or fantasized others.

Perhaps the most important thing we can do is to acknowledge the risks. To consider the power we hold, and what it might mean to our subjects to find themselves depicted as we have depicted them. To ask ourselves how we might feel, to find ourselves depicted that way—although that’s tricky, because I think as writers we’re generally sensitive to point of view and to shifting or layered narrative perspectives that might not be apparent to more naïve readers.

In the case of memoir, I think we also need to consider the truth. Naturally, there will be differences in how different people perceive and remember a situation, but if you claim that your mother regularly beat you when in fact she was meeker than a lamb and never raised so much as an apron string, that’s a breach of your reader’s trust as well as your mother’s. An extreme and easy example—but in the last few years, we’ve seen far wilder claims—and they give memoir a bad name.

But here’s the wrinkle: It’s entirely possible for someone to experience a meek mother as a monster. And that is humanly interesting. But the story isn’t about the monster mother, or even about that it is like to have a monster mother. The story is about how it is possible to experience a meek parent as a monster. It should be an exploration, not a melodrama.

The thing is…explorations are never simple. And people are sometimes threatened by complex stories. They want the simple version. The simple version is familiar.

Not only are we threatened by complicated stories, but we also struggle to express them. It’s much easier to tell (and sell) a beginning-middle-and-happily-ever-after narrative about How I Lived with My Monster Mother than it is to tell the story of your evolving feelings and your changing perceptions of your fairly ordinary mother, who turns out not to have been quite the monster that you initially thought.

But it’s literature’s responsibility and privilege and glory to tell these complicated stories and to explore messy truths—the kind that many of us run away from in our day-to-day lives. And ideally, in order to prevent simple narratives from driving out complex narratives, we need to find ways to incorporate our own self-doubts and confusions into the work. The essay is a perfect form for that.

One of the most instructive aspects of this book for me was the story of your daughter’s adoption. This was an international adoption, and you describe travelling to China to meet your child for the first time. But because this book spans such a large segment of your life, the story doesn’t end there. Instead, we follow you and Maia for several years as you struggle and work through the reverberations of what it means to have started life in the way that your daughter did (you describe the neglect and abandonment she was subjected to in the first ten months of life). Perhaps you could talk about the decision (if that’s what it was) to present Maia’s arrival into your life not simply as a happy ending, but, I suppose as a new chapter.

I like that phrase, “a new chapter.”

And you’re right, I did make a decision not to stop at the “happy ending” of adoption. This goes back to my answer to your earlier question. Having lived for a few years with our daughter, I felt the dominant narratives about adoption were overly simple. (Perhaps this applies to all parenting narratives, to some degree, especially narratives about the early years of parenthood.)

Anyway, I didn’t see our family or families like us represented in anything I read in the media or in the children’s books or even in the novels I had seen up until then. Typically, adoption is either sentimentalized as an answer to everyone’s prayers, or it is dismissed as an inferior way to form a family. I wanted to tell one story of what it is really like in all its messy wonder.

The anxiety of writing about others, and especially your daughter Maia, comes to the fore in the essay “Mama’s Voices.” This is such a strong piece of writing for so many reasons.

Thank you! And thanks also to Fiona Tinwei Lam, (http://fionalam.net/) who encouraged me to write this piece. She and her co-editors had already accepted a proposal for a completely different piece to be included in Double Lives: Writing and Motherhood, but when she heard the story about my experience at a writing conference, she urged me to switch tracks and write about that instead.

Click here to read Part II of the interview with Susan Olding.

[Photo: Susan Olding]

CNF Conversations: An Interview with Susan Olding (Part II)

Susan Olding, Pathologies: A Life in Essays. Calgary: Freehand Books, 2008.

*

This is Part II of a two-piece interview with author, Susan Olding. Click here to access Part I.

Julija Šukys: You describe leaving Maia for the first time– it’s not an easy thing to do, but necessary and desirable for your work. There, after having received positive feedback regarding an essay you’ve written about Maia, you decide to change course and run with the idea of writing a book about your relationship with her. When you workshop this idea, you find yourself harshly criticized by fellow writers and even a revered memoirist and mentor, who compares your project with her own unsavoury idea of writing a book about a pedophile. I recognized so many of my own anxieties and experiences in this piece. Please talk a little about your view and experience of writing and mothering. How did becoming a mother change your relationship to writing?

Susan Olding: In the short term, it made it a lot harder to get any work done!

But over time, it has been the greatest thing possible for my writing life. First, because our daughter brings enormous joy into our lives, and joy begets joy. Also, at times she’s been a muse. And she has taught me so much about myself and my limits, and also about creativity. She’s profluent and spontaneous in a way I’ve never been, and it’s such deep pleasure to share her in her quicksilver spirit. I’m so grateful to be her mother.

You point to how writing about one’s own life is sometimes seen as unseemly, solipsistic, narcissistic. It can be, but it doesn’t have to. What, in your view, is the piece that sets successful autobiographical writing apart?

Successful autobiographical writing invites readers to draw comparisons to their own experience; it prompts and provides occasion for a kind of deep reflection that may be increasingly rare in our fragmented lives, and reminds us of where we stand in a historical or cultural context. Somehow, it affirms the possibility of making meaning. So it’s all about the author—and yet not about the author, at all! Strange paradox.

How does this work? Subtext, subtext, subtext. Language and structure create this subtext. Which is why Virginia Woolf, in “The Modern Essay,” counsels that it is “no use being charming, virtuous, or even learned and brilliant into the bargain, unless…you…know how to write.”

Adam Gopnick claims that the memoir and personal essay are actually the least self-indulgent of genres. You can’t get away with flourishes or padding if you are writing about yourself.

You have changed some of the names in the book and have retained others, like Maia’s. How do you decide when to do this? Do you allow the people you write about any veto power?

My decisions about retaining or changing names weren’t terribly systematic. I went with my gut.

I asked the people I’m closest to—my husband and my daughter. Of course I knew there was no way to get anything like “informed consent” from an eight year old, but Maia knew generally that I had written about our struggles, and her decision to go by her own name seemed consistent with her character. Right now she is pre-teen shy, and would probably balk, but in general she is a very open person and always has been.

I also asked several friends. Most chose to go under their own names but a few preferred to remain anonymous. I respected their wishes.

I changed students’ names and a few identifying features so they wouldn’t be recognizable and their privacy would be preserved. These people didn’t know I was writing about them; it didn’t seem fair to identify them by name; nor, for that matter, did it seem necessary.

As for my parents, I felt their privacy was already protected to some degree (among strangers) because I don’t share their surname. For extra protection, I changed their first names.

I gave veto power only once, to my brother, for “On Separation,” the piece about my sister-in-law, and I also asked him if I should change her name. He generously allowed me to publish and encouraged me to retain her name because he felt she would have liked that.

Do you still worry about hurting those you write about?

Of course! Although “worry” probably isn’t the right word. I hope I won’t hurt those I write about. And I do my best to prevent that. But I have in fact hurt people that I’ve written about, and suspect I may do so again. And ultimately, I’m loyal to the work.

I want to touch on the issues of critique and courage. I found the description of your devastation and confusion in the face of you peers’ criticisms very moving. The workshop participants (fellow writers) told you that it would be unfair to write about your daughter, and that you risked ruining her life by doing so. After sometime, you came to the conclusion that, despite their objections, you had to or wanted to write about her anyway. I think that this essay tells some deep truths about the writing process: both about how vulnerable writers are, but also how fierce. Even when we are racked with self-doubt, every writer who manages to bring a big project like a book to fruition also needs to have a rock-hard belief in the value what she does. How has that moment of doubt, after you received such criticism for your plans to write about your daughter, shaped your subsequent work and way of thinking?

Such a good question.

The simple answer is that I have not written the book that I proposed to write at the conference. Because in a way—and this is the hardest thing to acknowledge—that teacher was right! It wasn’t the right time to write a book about Maia.

Not because I might ruin her life. Not because it would say something awful about me as a person if I chose to write it. But because I wasn’t ready. And on some level, I recognized this at the time, and my recognition made my peers’ objections and the teacher’s objections cut more deeply. For the fact is, if I had been ready, nothing they said would have stopped me.

I may never be ready. Strangely, perhaps, that possibility doesn’t bother me. The need to write that particular book has passed. I have sometimes mourned other “lost” books—the novel that I set aside 100 pages in, the book of poems that I didn’t manage to finish. But I don’t mourn the book about Maia.

Having said all that, although I may not have written a whole book, I did write about my daughter. And I published what I wrote. So in that sense, I ignored what my critics said. I also wrote about the conference itself. Did I say writing well was the best defence? It’s also the best revenge. [Insert evil chuckle.]

Seriously, though—I hope there’s enough irony in “Mama’s Voices” to suggest that while my hurt was real, and to some degree justified, I also see humour in the situation. The essay includes a parallel narrative about Lana Turner, queen of the melodrama. I had my own little melodrama going on in that workshop!

But “fierce” is such a great word; we really do have to be fierce. People will tell us that what we’re doing can’t be done, or shouldn’t be done, or that we’re not good at it, or that it isn’t worth doing. And usually, we’re advised to ignore these critical voices. But I don’t believe we can ignore them. Or at least I can’t ignore them, so I’ve made necessity a virtue.

I say we need to learn to listen, for blanket criticisms can disguise meaningful objections, and we need to cultivate enough humility to recognize when that’s the case. At the same time, we need to hang on to some sense of the worth of what we’re doing. And we need to trust our own inner vision, and constantly measure our work against our felt sense of the beautiful and the true.

“My own criticism has given me pain without comparison beyond what Blackwood or the Quarterly could possibly inflict,” said Keats— “and also, when I feel I am right, no external praise can give me such a glow as my own solitary reperception and ratification of what is fine.”

But it’s an incredibly delicate balance—to remain open to critique while at the same time holding fast to the essential value of what we are doing. The test I sometimes use: Would I want to read this? If not, then I shouldn’t foist it on others. If yes, then I need to keep working on it until I get it right.

Last question: your form is the essay. Conventional wisdom in the writing/publishing community says that essays don’t sell and that the form is unsexy. Tell me about how you came to be an essayist, and what you think the form has to offer.

Conventional wisdom is right; essays don’t sell! At least they don’t sell when the author is an unknown writer. I was thrilled when Melanie Little at Freehand took a chance on this collection.

But why don’t essays sell? It’s a mystery. Maybe it’s even a lie. Because they do sell, in anthologies. Look at how well the Dropped Threads series (and others) have done. Most of the pieces in those anthologies are essays of one kind or another, although typically they are less deeply exploratory than the best writing in the genre. Still, readers love them. And readers also continue to respond to classic essays by Virginia Woolf, George Orwell, and many more. So the form is very much alive, even if writers can’t make a living from it.

Is the essay my form? Actually, I write fiction and poetry, too. It’s just that, in general, I’ve been less satisfied with my work in those genres and haven’t published as much of it (see above). But you’re onto something, because I think I’m an essayist by temperament and inclination. A born questioner and self-questioner.

It’s arguable, but the essay may be our most intimate form. Reading one is a bit like reading a letter from a friend, and in fact, some people believe that Montaigne began writing his essays because he could no longer converse with a dear friend who had succumbed to the plague. Essays can be playful or deeply serious (or both at once); they can be concise or expansive; they can be lyrical or logical. Always, they invite the reader to share in an exploration of some kind. You never know where you’ll end up when you set out, or what you’ll see, but you do know that the author will show and tell, and you will think and feel, that no part of you will be left behind or set aside.

I love the form. I loved it long before I knew its name. That may not sound sexy to publishers, but it sure sounds sexy to me!

Louise DeSalvo’s List: Criteria of a Completed Memoir

One of my first Life-blood posts was a short review of Louise DeSalvo’s essay, “A Portrait of the Puttana as a Middle-Aged Woolf Scholar.” I came across that piece in my search for some frank and honest discussion by women about mothering and writing. My son was still very little (around two), and I was struggling to balance my writing life with the demands of raising a toddler. I wanted to know what older, wiser mother-writers had to say about the matter. DeSalvo’s essay is one of the best things I’ve read on the subject.

Since, then, I’ve learned more and more about Louise DeSalvo. In her long career, she’s transformed herself from a Virginia Woolf scholar to renowned memoirist. Her books include Vertigo, Breathless, Adultery, Crazy in the Kitchen, and Writing as a Way of Healing. She has long taught writing (specifically the craft of memoir) at Hunter College in New York.

This is all to say that DeSalvo keeps one of the best blogs I’ve seen on writing as craft, process, and a way of life. Her most recent post, dated May 3, 2011, examines the mechanics of memoir. In it, she recounts a conversation with a person she “does her best to avoid” who scoffs at the idea that memoir too has a form that successful writers must take account of. In response to this individual’s challenge (and scorn), she comes up with a list of twenty criteria of a completed (successful) memoir. Here’s a taste, taken from her list of 20:

Visit Louise DeSalvo’s blog for seventeen more. You won’t regret it.

[Photo: miss niki chan]

Life-blood: Louise DeSalvo

Louise DeSalvo, “A Portrait of the Puttana as a Middle-Aged Woolf Scholar.” Between Women: Biographers, Novelists, Critics, Teachers and Artists Write About Their Work on Women (Routledge, 1993), 35-53.

I love this essay for many reasons.

1) It’s a seriously learned text written in a light and readable first-person voice.

2) It tells a story about being a woman that doesn’t reduce our existence to beauty (or lack thereof), procreation (or lack thereof), or our relationships (or lack thereof) to men.

3) It’s about the pleasure of archival work and falling in love with a woman writer who lived long ago.

4) It’s about growing up in an immigrant family and making your way intellectually in the language (and culture) of the new land in a new way.

5) It’s about how Virginia Woolf can save your life. Still now, in 2010.

I came to Virginia Woolf embarrassingly late in my life. By the time I discovered her, or rather by the time I re-read her in a frame of mind that allowed me to be deeply moved, I was in my thirties and had a small child.

Louise DeSalvo describes a similar experience. Her essay starts: “I am thirty-two years old, married, the mother of two small children [. . .].” Travelling to England on research with a friend, and without her family, she and her companion represent “[t]he next generation of Woolf scholars, in incubation. We are formidable” (35).

The essay explores the role of women among DeSalvo’s Italian parents and their peers, and their relationship to food and men. Both, she warns, tell you a lot about what was expected of her and the many ways in which she was a disappointment.

First: women who care about their families, she says, make fresh pasta every day — a process that takes hours, and ends up enslaving the person saddled with the task.

Second: women who do anything without their husbands are puttana — hence the essay’s title, and the opening scene on the plane.

Instead of a dutiful, stable, ever-cooking mother, DeSalsvo becomes a “whore,” a woman who lives her own life alongside her husband and children. A woman who does things without her man.

She narrates her own experience of the dichotomy of woman-writer (or woman-creator) that Woolf wrote about in her essay A Room of One’s Own, and the hope this text continues to offer to the despairing and frustrated among us.

She tells about loving a child and a husband, and at the same, loving reading, writing and writers.

Ultimately, this is an essay about how literature can change us in fundamental ways. For many of us, writing is no hobby or even profession. It is our vocation, our life-blood, the very thing that keeps us alive.

“Woolf taught us that writers are human beings, that writing is a human act, that the act of writing is filled with human consequences for a society and for its readers. No ‘art for art’s sake.’ Instead, ‘art for the sake of life'” (52).

[Photo: jspad]