Here’s a list of books to use when teaching CNF. It’s not exhaustive, but it’s a good start. This list originally grew out of a discussion by members of the Creative Nonfiction Collective (CNFC). Members of “Essaying the 21st Century” (on Facebook) have added to it as well. If you have suggestions, feel free to send me a note or add a comment.

Atkins, Douglas. Tracing the Essay

Barrington, Judith. Writing the Memoir

Birkerts, Sven. The Art of Time in Memoir: Then, Again

Bradway, Becky and Hesse, Douglas, eds. Creating Nonfiction: A Guide and Anthology

Castro, Joy. Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazards and Rewards of Revealing Family

D’Agata, John, ed. Lost Origins of the Essay

–, ed. The Next American Essay

DeSalvo, Louise. The Art of Slow Writing

–. Writing as a Way of Healing

Fakundiny, Lydia, ed. Marcela Sulak and Jacqueline Kolosov. The Art of the Essay

Forché, Carolyn and Gerard, Philip. Writing Creative Nonfiction: Instruction and Insights from Teachers of the Associated Writing Programs

Gornick, Vivian. The Situation and the Story.

Gutkind, Lee, ed. In Fact: The Best of Creative Nonfiction

–. You Can’t Make This Stuff Up

Iversen, Kristen. Shadow Boxing: Art and Craft Creative Nonfiction

Kaplan, Beth. True to Life: 50 Steps to Help You Tell Your Story

Karr, Mary. The Art of Memoir

Kidder, Tracy and Todd, Richard. Good Prose, the Art of Nonfiction

Lazar, David, ed. Truth in Nonfiction: Essays

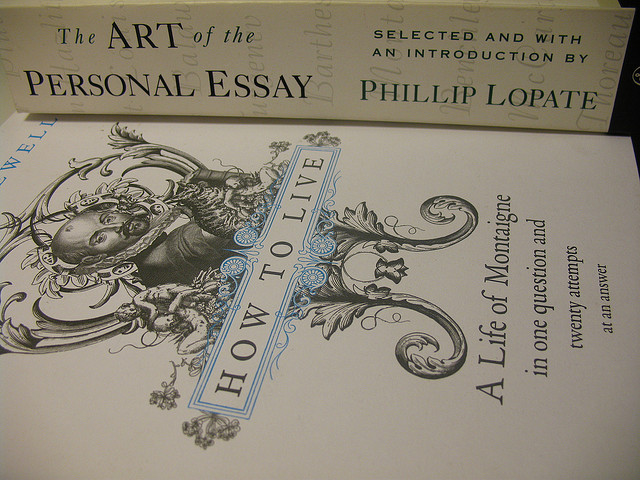

Lopate, Phillip, ed. The Art of the Personal Essay

–. To Show and To Tell: The Craft of Literary Nonfiction

MacDonnell, Jane Taylor. Living to Tell the Tale

Miller, Brenda and Paola, Suzanne. Tell it Slant

Moore, Dinty. Crafting the Personal Essay: A Guide to Writing and Publishing Creative Nonfiction.

–, ed. The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction: Tips from Editors, Teachers, and Writers in the Field

–. The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction.

Rainer, Tristine. The New Autobiography

Root, Robert. The Nonfictionist’s Guide.

Roorbach, Bill. Writing Life Stories

Silverman, Sue Williams. Fearless Confessions: A Writer’s Guide to Memoir

Sims, Patsy. Literary Nonfiction: Learning by Example

Singer, Margot and Nicole Walker, eds. Bending Genre: Essays on Creative Nonfiction

Sulak, Marcela and Jacqueline Kolosov. Family Resemblance: An Anthology and Exploration of 8 Hybrid Literary Genres

Thompson, Craig. Blankets

Tredinnick, Mark. The Land’s Wild Music

Williford, Lex and Michael Martone, eds. Touchstone Anthology of Contemporary Creative Nonfiction: Work from 1970 to the Present

Yagoda, Ben. Memoir: A History

Zinsser, William. Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir

–. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction.