I arrived home from a week of camp with my three-year-old to learn that the University of Toronto is threatening to close the Centre for Comparative Literature, where I earned my PhD.

If you are engaged in writing and reading, if you value creative thought, innovative teaching and scholarship, and believe in cross-cultural dialogue, please write to the university in support of the Centre. The relevant email and postal addresses appear below.

Here is the text of the email bearing the distressing news:

Dear Alumni of the Centre for Comparative Literature,

As a fellow alumna of the Centre, I am writing to inform you of some very distressing news and to solicit your support. The University of Toronto has recently and unexpectedly announced the “disestablishment” of the Centre for Comparative Literature as of 2011. The Centre, founded in 1969 by Northrop Frye and the premier site for the study of Comparative Literature in Canada, will no longer be able to admit students to the PhD or MA degrees. It will be reduced to a collaborative, non-degree-granting program in a future School for Languages and Literatures, a proposed new unit that will be formed by the fusion of all current language and literature departments except French and English. For all intents and purposes, the Centre will cease to exist: all core faculty will lose their cross-appointments, no Comparative Literature courses will be offered, we will no longer have our offices, our space, our director and graduate coordinator, or our identity. The proposed disappearance of the Centre will undoubtedly have an extremely negative impact on the future of the discipline in Canada and it reflects the general depreciation of the humanities and their essential contributions to knowledge and society. I should add that the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto is presently flourishing, with a cohort of excellent, motivated students, an innovative curriculum, a prestigious annual international conference organized by our students, and a number of exciting initiatives, such as the journal Transverse www.chass.utoronto.ca/complit for details). The decision to close the Centre thus has absolutely nothing to do with the current state of the unit and everything to do with budgetary concerns and an ignorance of the discipline.

This disastrous course must be averted for the sake of literary and interdisciplinary studies in Canada. On behalf of all faculty and students in the Centre, I am writing to ask if you would be willing to send a letter to President David Naylor of the University of Toronto, registering your concern at these proposed events.

If you write, we would be grateful if you could discuss the importance and relevance of Comparative Literature in today’s globalized, multicultural world. In its crossing of cultural, disciplinary, and linguistic borders, in its self-reflexive and critical modes of thinking about literature and culture, the research nurtured by the Centre’s faculty and students is crucial for a full engagement with the complexities of a multipolar, multinational world, and is a model for the practice of the humanities in other disciplines.

If you do send a letter, please send a hard copy as well as an e-mail. The hard copy should go to:

President David Naylor

University of Toronto

Simcoe Hall, Room 206

27 King’s College Circle

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 1A1

The e-mail message should go to: president@utoronto.ca

Please copy the e-mail to the Provost Cheryl Misak (provost@utoronto.ca), the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science, Meric Gertler (officeofthedean@artsci.utoronto.ca), and the Director of the Centre for Comparative Literature, Neil ten Kortenaar (neil.kortenaar@utoronto.ca).

I thank you kindly for your prompt attention to this request and for the time you will spend in composing your letter. It is our sincere hope that if enough of us express our outrage at this decision, it will be reversed.

Yours sincerely,

Barbara Havercroft

Graduate Coordinator, Centre for Comparative Literature

(PhD 1989 from the Centre)

Below is one thoughtful letter that argues in favour of keeping the Centre open. If it helps you write your own letter, please feel free to mine it for content and ideas.

Dear President Naylor,

I have just received news from friends at the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto, where I was proud to be a graduate student and from which I received my PhD in 2001, that the University intends to “disestablish” Comparative Literature as a degree-granting program as of 2011. I am not a faculty member at the University of Toronto, so of course I have not seen the official documents, but if it is true that the university intends to take a series of actions that will in effect end the Centre’s existence, then this is a profoundly depressing development, and more than a little embarrassing to the university of which I have until recently been a very proud alumnus. I urge you to consider alternate options. The Centre is an important part of the history of the University of Toronto and of Canadian scholarship in the humanities; it is a rigorous and flourishing program; and its loss will mean a significant demotion of the University of Toronto in the eyes of the international community of humanities scholars.

The University of Toronto has had a long and important role to play in the humanities in Canada and internationally, but perhaps the single most important series of contributions were made by the literary theorist Northrop Frye. His impact across all of the humanities can hardly be underestimated, and the spirit in which he conducted his research – a ravenous curiosity, a powerful command of the central texts of the Western tradition, and a humane and often humorous style of presentation – has influenced nearly every scholar who has made a contribution to literary studies in the last 50 years. He was instrumental in founding the Centre for Comparative literature at the University of Toronto, and in an important way the Centre is synonymous with his legacy. I cannot imagine how doing away with such a central element in the University’s heritage will not be seen as a remarkable rejection of the legacy of one of its most brilliant scholars.

I chose the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto over a number of other very strong programs in the United States because in addition to its history, it hosted scholars of great international stature with whom I was very eager to work, and in the time that I have been active as a scholar this has continued to be true. My own supervisor, Brian Stock, was affiliated with the Centre until his retirement and has been an honorary member of the Collège de France and, now, of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Also recently retired, Linda Hutcheon, distinguished University Professor and 2010 winner of the Canada Council for the Arts’ Molson Prize, has published a spectacular series of profound and influential studies, served as the president of the Modern Languages Association, and was also elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. These were the faculty members with whom I had the most contact when I was a graduate student there in the late 1990s: they were only part of a complement with wide international influence and a deep and important legacy. That the Centre should be “disestablished” so soon after their retirement sends a message about the value the University puts on their life’s work; a message they will not hesitate to share with their friends and colleagues internationally. The current faculty is no less strong, and I have seen the vibrancy of the Centre myself in recent years. Its students continue to distinguish themselves: in the last year alone, one received a prestigious Vanier Scholarship, and another one a Governor General’s Gold Medal for best dissertation.

None of the work of the scholars I just mentioned could have been done without the context for interdisciplinary exchange and the creative exploration of new ideas that the Centre has traditionally supplied. My own career has been profoundly shaped by the unique combination of intellectual rigor and creativity that the Centre inspired. With the Centre’s loss, this kind of research simply will not happen, and the University will be weaker for it.

It also means that the University of Toronto will lose a significant source of international visibility. Comparative Literature departments and centres continue to be major drivers of innovation in the humanities, and comparatists push the agendas of many humanities scholars, even those who do not hold comparative literature degrees. Indeed, a large proportion of the most influential studies in the last ten years have been produced by scholars affiliated with a department of Comparative Literature. Having such a department, and the path-breaking research that goes with it, is one of the signs that a University is serious: shutting one down tells the world that the University no longer considers itself so.

I write not only as an alumnus of your University and as a scholar who continues to have warm and productive relationships with many colleagues there, but also as a Torontonian with a deep emotional connection to the UofT. At my current University’s convocation ceremonies, I wear the UofT hood proudly, and I often urge my undergraduates to count the UofT among their top choices for graduate school. The proposed “disestablishment” of the Centre for Comparative Literature, if it happens, will make all of that a little more difficult. Please reconsider.

You can read more about the Centre’s predicament in The Torontoist.

Click here for an UPDATE on the situation at U of T Comp Lit.

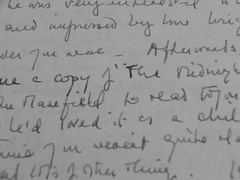

[Photo: eriwst]