Delivered on December 12, 2022, in Toronto. By Julija Šukys.

What I know about survival, courage, and joy, I learned from my mother. Vida taught us, her children, that life is adaptation, that peace comes through the acceptance of change, and that it takes courage to live with joy.

She would chuckle when I pretended to be stern and told her to “assume the position,” so I could get her dinner tray in place, strap it to the arms of her wheelchair, and settle in with her for a Sunday night murder mystery on TV. She would laugh as a boyfriend and I struggled to get her up off the floor after she’d toppled over onto her bedroom carpet. And even after dementia had settled in and she’d pretty much stopped talking, I could still make her giggle by giving her a series of loud kisses on her cheek.

Our mother’s diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis came more than 40 years ago, when I was about 4 and my brother, Paul, about 6. It started one day at work, my mother told me. A high school science teacher, Vida was eating lunch in the staff room when half her face suddenly went numb. Many MS patients tell horror stories of years of tests and misdiagnoses, but Vida was the exception. Her diagnosis came quickly and without delay. “When they told me what it was,” she said, “I thought, well, at least it doesn’t kill you.”

About eight years ago, I interviewed my mother about her life and her illness. We talked in the library of her nursing home. “The facial numbness disappeared after a while,” I hear her say on the tape I made that day. She goes on to describe other effects that emerged over the years: double vision, fatigue, imbalance, and unresponsive limbs.

Near the end of our recorded conversation, Vida finally lands on the thing she told Paul and me for years. Call it a mantra of sorts: “I had this philosophy that I wouldn’t dwell on what I’d lost, but I’d look at what I could still do and expand on it with multiple aids. And then,” my mother concludes, “if I did that, I was a winner.”

Vida was so good at making the adjustments that MS required of her that, in my view, her defining characteristic wasn’t her illness but rather her extraordinary response to it. “This is a class act,” wrote the essayist Nancy Mairs, “No tears, no recriminations, no faintheartedness.” Though I’m pretty sure she had never read or even heard of Mairs, who also suffered from MS for decades, Vida unwittingly lived by her words.

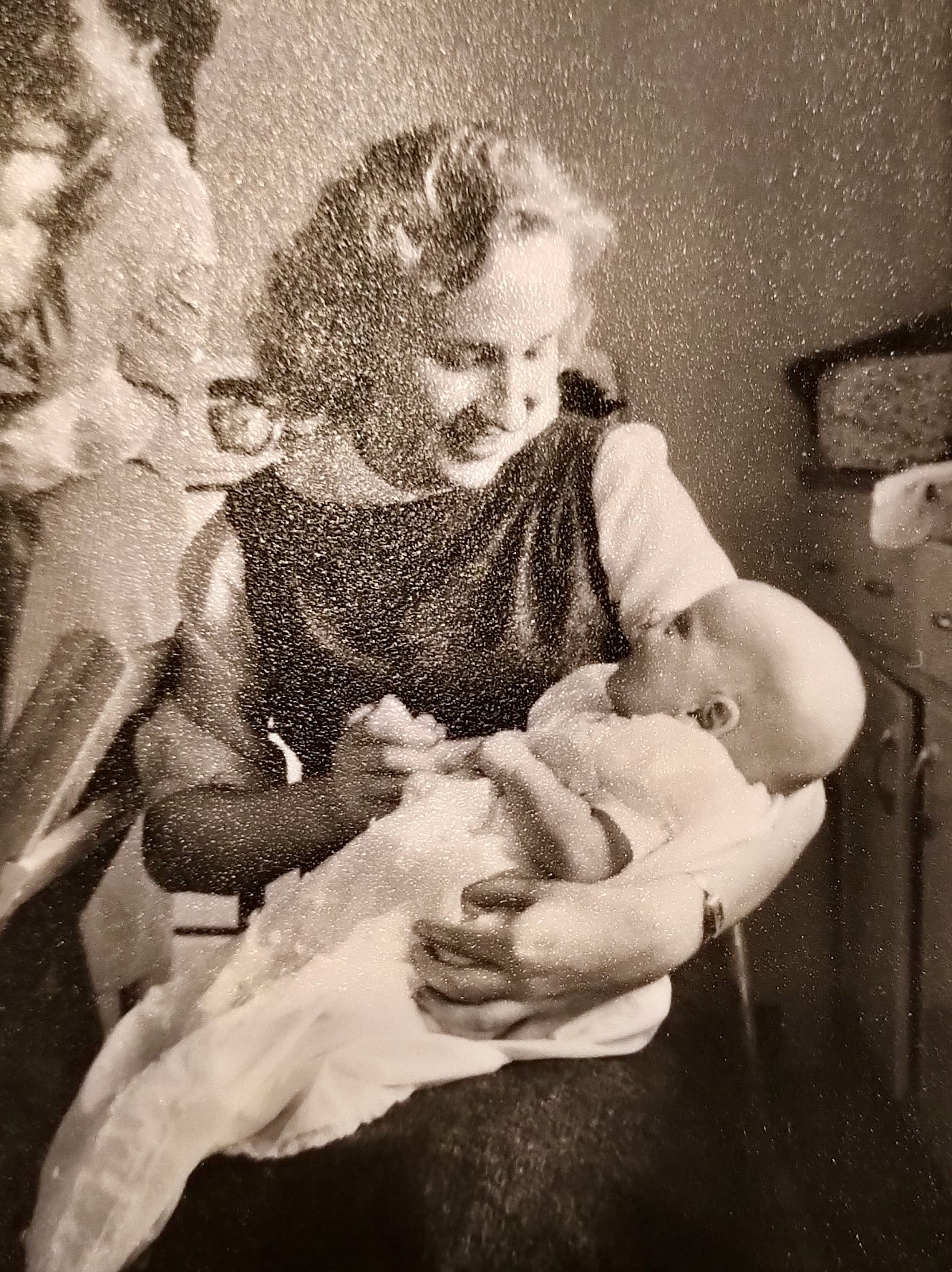

Sitting vigil with my mother in her final weeks has been one of the great honors, joys, and sorrows of my life. Each day when I arrived, I would give her noisy kisses, rub her legs, and hold her hands. Each day, I would say over and over again, “Hi Mama. I’m here. I love you.” I must have said it a thousand times.

In the days since her death, I’ve felt like a planet knocked out of its orbit. And I’ve marveled at a new realization: That despite her illness, Vida was like the sun around which my brother and I revolved. She was at the center of everything; the magnet that pulled me back to Toronto at every opportunity. Somehow, although her body and even her voice no longer worked, she still managed to be the strongest force in our lives. I feel a bit lost without her. I have no doubt that Paul does too.

But our mother taught us well. She passed on lessons about self-transformation and survival, so we will adjust. We will take care of each other now.

Mama, we’re here. We love you.

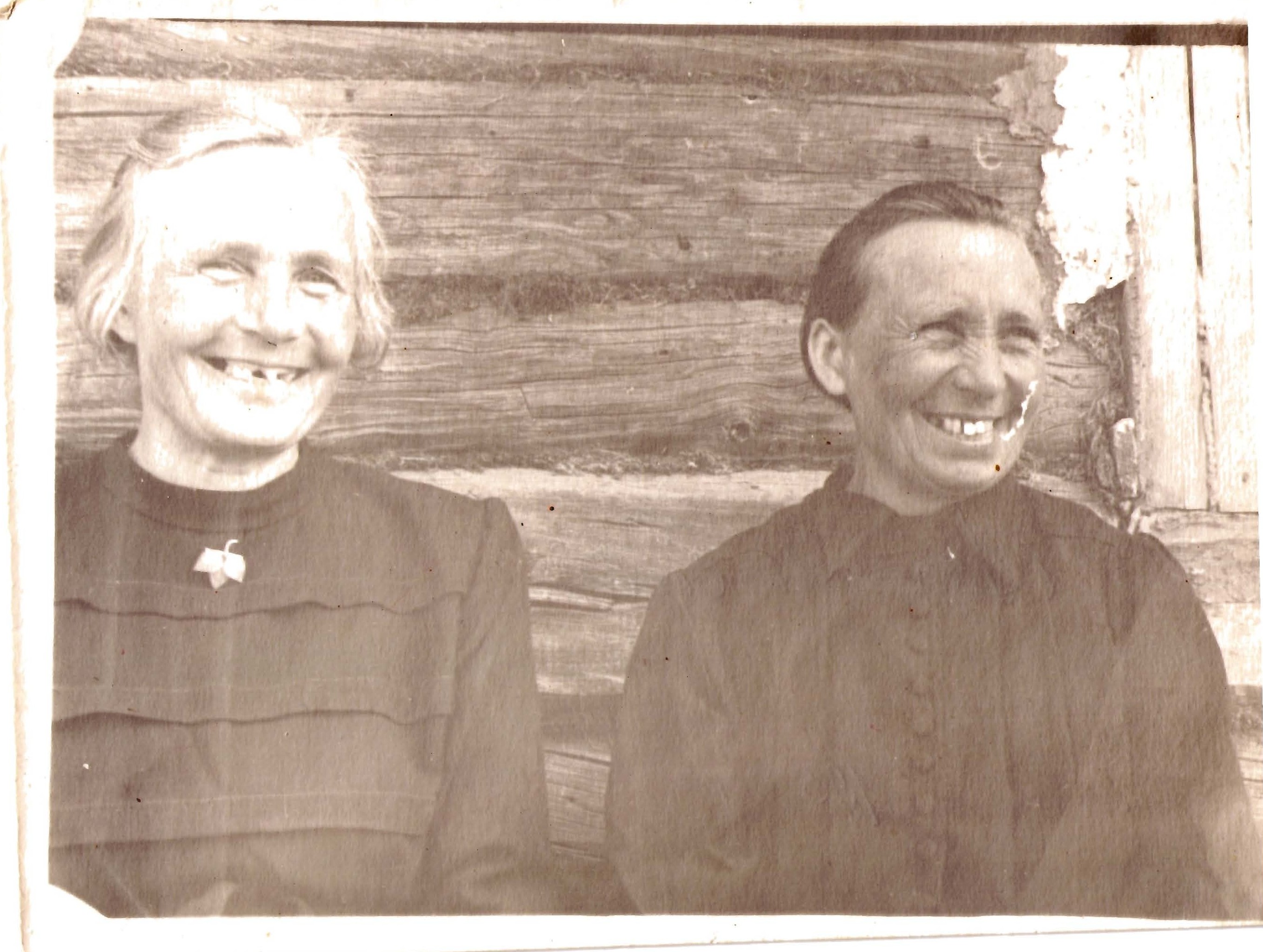

Go to your ancestors and walk with them again. They’re waiting for you, I’m sure.

For most of my life, my relationship with Aunt B. was polite and cordial, but not close. This changed when I began to write about our family. The project gave us a chance to bond over a shared purpose and, over time, I began to feel our mutual sharpness soften. She and I started spending hours at her kitchen table, looking at photographs, talking about life in the displaced persons camps and how it felt to meet her mother when she finally arrived in Canada, after so many years of separation. We took to talking on the phone regularly. I liked that Aunt B. and I were partners in this, so I began sending her updates on my work.

For most of my life, my relationship with Aunt B. was polite and cordial, but not close. This changed when I began to write about our family. The project gave us a chance to bond over a shared purpose and, over time, I began to feel our mutual sharpness soften. She and I started spending hours at her kitchen table, looking at photographs, talking about life in the displaced persons camps and how it felt to meet her mother when she finally arrived in Canada, after so many years of separation. We took to talking on the phone regularly. I liked that Aunt B. and I were partners in this, so I began sending her updates on my work.