This is Who-Man. My son and I invented him over breakfast this morning.

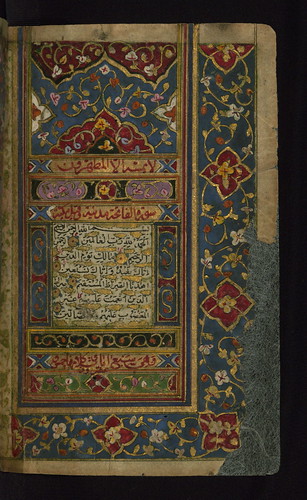

Who-Man is a superhero whose arch-enemy is a many-eyed monster called “Crime.” Who-Man wears a bumpy suit (as you can see in Sebastian’s rendition of him above). The suit can shoot fire, but our hero rarely has to use this weapon. He has other ways of defeating his enemies: confusion.

Here’s an example of one of his crime-fighting encounters:

Who-Man hears a bank’s silent alarm and rushes to the scene of the crime. He succeeds in intercepting the robbers just as they are about to jump into their getaway car.

Who-Man: Stop! In the name of Justice and Who-Man!

Robbers: In the name of who?

Who-Man: Who-Man!

Robbers: What?

Who-Man: No, Who!

Robbers: Who?

Who-Man: Yes, that’s me! Who-Man!

Robbers: Oh man, what?

And so on until they’ve wasted so much time that the police arrive and arrest the bad guys.

Sebastian was laughing so hard when we acted this scene out that he could barely talk (he’s definitely ready for “Who’s on First”). Then he said “Let’s write a a book about Who-Man! We can make the first page right now!”

As we giggled and added detail upon detail to our story, I had a feeling in my chest that I recognized. It was the elation of creativity and play. It’s the way I feel when my writing is working.

When I started writing my first book, I spent months reading and researching and sitting on my hands, trying to resist the scholarly impulses that graduate school had hammered into me. I had just completed my PhD, and won a coveted postdoctoral fellowship. I should have written a dry literary study, gotten myself a tenure-track job, and settled into a life of literary analysis. But no.

Instead, I wanted to write something that could never be mistaken for an academic book. I decided not to give in to my training (better to write nothing than to write stuff that made me unhappy, I reasoned), not shush my creative impulses, and allowed myself to do some preposterous things. Some of the more insane ideas got cut during the editing process, but others were just crazy enough to work.

Fun and play are not concepts that would naturally be associated with the kinds of books that I write, because so far, I’ve only written about tragedies and atrocities. (Though Who-Man may change all that!)

For example: my first book (Silence is Death) is about an Algerian author who was gunned down outside his home at the age of 37 in a growing wave of violence against artists in intellectuals during the 1990s. My second (Epistolophilia) is about the Holocaust in Lithuania, and my third (working title: Siberian Time) will be about about Stalinist repression.

Nonetheless (and at the risk of sounding psychologically unbalanced), one of the ways I know I’m on to something good is that I start having fun.

In Silence is Death, I wrote a posthumous interview with Tahar Djaout, the subject of my book. A chapter of almost pure invention (though I still had to do a lot of research), it was great fun to write. I visited then wrote about shrines full of saints’ bones, interviewed nuns about the meaning of relics, and dragged my husband on a weekend trip to a funny little Iowa town called Elkader that was named for the Algerian national hero, Emir Abdelkader. All of this made its way into that first book, which turned out to be my first big step into creative nonfiction.

For Epistolophilia, I recorded the trips I made with my infant son to find my heroine’s various homes, including a French nursing home where Ona Šimaitė (the subject of the book) lived out her final years. I wrote about my pregnancy, compared the pronunciation of my heroine’s name to a Leonard Cohen song, and immersed myself in a friendship that only existed in my head. I circumnavigated the globe, collecting archival documents along the way.

That too was fun.

In the Guardian’s famous “Ten Rules for Writing Fiction,” (or nonfiction, for that matter) Margaret Atwood says, “Nobody is making you do this: you chose it, so don’t whine.”

I would add: enjoy it. Living a life of writing is a great privilege. Whatever way you manage to do it, remember to have fun (in the name of Who-Man!) and to play once in a while.

Your writing will be better for it.

[Image: Who-Man, by Sebastian Gurd. January 19, 2012]

This post is part of a weekly series called “Countdown to Publication” on SheWrites.com, the premier social network for women writers.