I’ve been working with archival materials for more than a decade now.

While writing my dissertation, I sat in archives comparing drafts of novels, tracking authors’ corrections and studying the process of composition and revision. More recently, I’ve been working on diaries and letters, telling the story of a life on the basis of private papers. Archival work can be slow and painful: you have to read some twenty or fifty letters before you find one that grips you, speaks to you, or tells you something new.

Piecing together a narrative from a million seemingly inconsequential details is the hardest literary thing I’ve done yet. You can’t know what will be important, so you have to copy everything, read everything, and take copious notes. The result is a lot of paper, loads of post-its, a stack of storage boxes as tall as me, and a chaotic office. Only after thousands of hours of reading and reflection will a thread start to emerge.

Waiting for the thread takes faith and patience.

Still, there’s little that thrills an archival researcher more than making a connection or accidentally finding a key piece of evidence: these moments of pleasure that make the pain worthwhile.

So here’s where I’m at: after years of work, of mastering my subject’s writings, and having finally completed my manuscript, it dawns on me that I don’t own this material. While writing my book, I had put the issue out of mind, but now that I’ve finished, it’s time to face facts.

And the fact is that it’s not mine to publish. Not yet.

The issue is copyright.

In order to cite from unpublished archival materials, international copyright law requires permission of the author’s next-of-kin. In the absence of an heir, you must prove that you have made a good-faith effort to find one.

To be fair, I have a long-standing and good relationship with the nephew of my main biographical subject who controls the copyright of ninety per cent of the material that is important to my book. But permission for the other ten per cent now needs to be secured. I waited to finish the manuscript before starting the permissions process, because only now do I know what’s important to my story

For the past two days, I’ve been writing emails and making cold calls to Eastern Europe in my good-faith effort to locate the heirs of the authors of additional archival documents I cite.

And although it’s going well, the realization that I’d written a book that I might not be able to publish kept me up all last night.

This is the panic of archival work.

May the heirs be kind and generous.

Fingers crossed.

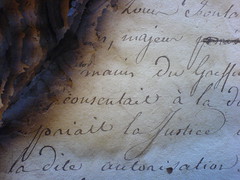

[Photo uploaded by anvosa]