A while back, in response to a question posed by a friend, I posted a few thoughts on what constituted creative nonfiction. Since then, I’ve been trying to think a bit more systematically about the genre, and to unpack my own writing process.

In that first entry, I cited Lee Gutkind, the editor of the journal Creative Nonfiction. Here too, I will turn to him, and a really lucid essay in which he breaks the genre down into components he calls the “5 R’s.”

Gutkind’s schema is pretty snappy and it makes sense to me. According to his model, the building blocks of CNF (I really like this abbreviation, and have started using it) consist of:

1) Real life

2) Research

3) Reading (not only research materials, he says, but masters of the genre and masters in general)

4) Reflection

5) (W)Riting

Gutkind’s is a pretty good description of how I work, though I might add one more R: “Rencontre,” by which a mean a somewhat mystical sounding meeting of past and present.

My work, for what it’s worth, tends to grow out of triangles. At the first of my three points, I have a fragment of the past; on the second there’s me in my here and now. The triangle’s third point is the the sense-making process between past and present, between my content and my perspective. The third point, in other words, is the point of the whole endeavour.

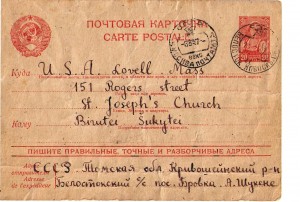

I always begin with a story (often a life) I want to tell, usually using an artifact like letters or diaries. Like, Gutkind, there’s always a real-life aspect to the research: I seem to get a better handle of how to make sense of worlds past by moving through the present. So, even though it’s not the same thing to go through Siberia by train in 2010 as it was in 1941, the trip nevertheless stimulates the imagination and raises questions.

Next, come research, analysis, and finally learning.

The best CNF doesn’t simply tell a story, but takes the reader on a transformative journey. And the easiest way to accomplish this as a writer is actually to learn something.

So, what are the components of my mode of CNF?

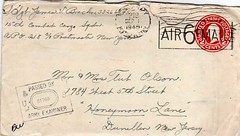

1) Story (This is my content, the first thing that tells me that there’s an original story to tell: a collection of letters or an untold life.)

2) Journey (I’ve not yet written anything half-decent without recounting a journey of discovery. Travel and observation are essential to my process. This is where detail and narrative drive come from for me.)

3) Questioning (Once I’ve got my content and have completed a journey of discovery, the important questions start to arise. I begin to figure out what the point of the story I’m trying to tell will be, and why not only I, but a reader, should care. Gutkind calls this stage Reflection.)

4) Research (Once I have a series of questions, I head to the library in search of answers. I read anyone and everyone who might be able to help. Much of this never actually makes it into the bibliography, but that’s OK.)

5) Learning (In some ways this is the hardest part, but it’s the piece that will make a CNF book worth a reader’s time. In order for the reader to learn, the author has to transform him- or herself in some way. For this reason, writing CNF requires humility. You can’t assume you know everything. If you do, there’s nowhere to go and nothing to learn.)

I continue to write at every stage in the process. Some parts of it are easier than others — journeys tend to write themselves, but incorporating research seamlessly can be like pulling teeth. I call that stage “writing through the pain.”

Weirdly, the final stage of learning often happens of its own accord. If you travel, watch, read, write and think for long enough, you’re bound to learn something. The trick is to listen carefully enough to hear what it is, and to write it down before it escapes.

So, if learning is the hardest part, how is it that it happens of its own accord?

Because you can’t cheat, fake or rush it. You have to do the work and put in the time for learning to come about. But when the point of the whole damn thing suddenly (that is, after months or years of work) reveals itself to you, and your manuscript seems to tell you how to finish it, writing becomes its own reward.

And then, for a moment, it may even seem easy.

How does your process work? Do the 5 R’s describe what you do?

[Photo: troycochrane]