*

Julija Šukys: My second question about language is about your relationship to the various tongues at work in this book. What is your relationship to Yiddish and Russian, the languages of your ancestor? Given the decline of Yiddish since World War II, there’s a real sense of loss that surrounds that language these days. Does this sense of loss come into play in your relationship to Gordin’s texts and history at all?

Beth Kaplan: Well, this is a very profound question because it also goes to the heart of my hybrid status – as a half-Jew delving into this very Jewish story. Several people, hearing of my work, told me I should learn Yiddish first. A Yiddish academic, who continued to be extraordinarily unhelpful, told me when I called to introduce myself at the beginning that writing a book about Gordin without speaking Yiddish was like writing about Moliere without learning French. As if my family connection were meaningless.

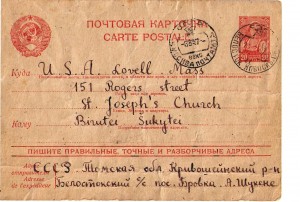

I had no interest in learning Yiddish, though I did take a term of Yiddish classes through the Toronto school board, where my suspicions were confirmed – the class was filled with people wanting to reconnect with memories of their childhoods, especially of their grandparents. I had no such desire. In fact, my grandmother, Gordin’s daughter, spoke no Yiddish and had no interest in it. That’s the irony at the core of all this, as you noted – Gordin, revered as a Yiddish playwright, spoke Russian or English at home and hadn’t much respect for the language of his great success. I did take Russian lessons, incidentally, which interested me much more because it’s the language of a country I could actually go and visit.

So it was thanks to my dear Sarah Torchinsky that the Yiddish documents revealed their secrets to me. My father, whose relationship with his own Jewishness was conflicted, as I point out in the book, loved Yiddish phrases and expressions and used them often, but he would have been horrified at the thought of actually learning to speak the language. Intellectuals like him thought of Yiddish, not as a vibrant language in its own right, but as a kind of hybrid, debased German.

I respect and admire those trying to keep Yiddish alive, especially the amazing Aaron Lansky of the National Yiddish Book Centre in Amherst. Right now, I am corresponding with a woman living in rural Texas, who speaks Yiddish in complete isolation and is translating one of Gordin’s plays. But the future of the Yiddish language is simply not my cause.

Although your portrait of Gordin is nuanced (you don’t hold him up as the best playwright who ever lived, nor do you sugarcoat difficult aspects of his personality like his ego), the book nevertheless reads as a project of rehabilitation. Gordin’s legacy has suffered terribly from a vicious campaign waged by the New York Yiddish literary critic, Abraham Cahan. Talk a little bit about the conflict between Gordin and Cahan. How much did you know about it when you began researching? What, in your opinion, lay at the heart of Cahan’s fervour in destroying his rival so thoroughly?

Abraham Cahan was a critic at the Jewish Daily Forward. The more I learned about his vindictive personality and especially his campaign against my ancestor, the more I felt that if nothing else, this book would defend Gordin and expose what he endured. I learned that Cahan pursued several other vicious vendettas, one against the writer Sholem Asch even more single-mindedly destructive than the one against Gordin.

I posit in my book that there was something about Gordin’s largesse, huge family (eleven children) and enormous popularity that goaded Cahan, who was the opposite in nature, an anti-social man with very few friends, no children and an unhappy marriage, who lived not in a home but in a hotel. So the surface of their battle may have been political – they disagreed vehemently on how Jews should be helped to adapt to their new land – but I think with a burning personal base.

When I found some of Cahan’s articles against Gordin and had them translated by Sarah, they broke my heart – they were so petty and cruel. Not without an occasional point, certainly – but far, far beyond the boundaries of criticism. They attacked everything about Gordin with a kind of nasty glee with made me, literally, feel ill.

You describe finding a number of Cahan’s assessments of Gordin’s work almost verbatim in current descriptions of his work, namely that his plays have little literary merit. To me (and I think to you), it is this question of tainted legacy (that of Gordin as a hack, and even, as you describe, of a plagiarist) that is the greatest tragedy of this story. What does Gordin’s story tell us about the capricious nature of literary legacy, or of how writers are made and destroyed?

I made a lot of the tragedy of Gordin’s humiliation by Cahan, because I did come to feel that Cahan had left an accusatory legacy of plagiarism that my father absorbed. But in the end, I have to point out that many people did remember and respect Gordin – that Cahan’s campaign wasn’t completely successful. After all, a quarter of a million people, apparently, packed the streets the day of his funeral. I think that Gordin was more a newspaperman or a teacher than a playwright, in that he was so didactic, always preaching his message. But an elderly Yiddish actor I spoke with from Britain told me his plays were spectacular vehicles for actors. I had to keep in mind how much the theatre itself has changed; that many of the most successful playwrights of a particular time vanish pretty quickly. Our list of great playwrights of other times is much smaller than the list simply of great writers; it’s hard to write a play that is relevant to its time but will also endure. Gordin was a marvel for his time and place, bringing theatre with dignity and finesse to a people who’d had no theatre at all only decades before and who only knew a kind of vaudeville of melodramas and operettas. He accomplished a great deal, but he was no Ibsen.

Most of my own contact with the Yiddish literary scene has been through my research on Vilna. I was amazed to learn of the vibrant Yiddish scene that Gordin was a part of New York at the turn of the century. Do you see echoes of that theatrical and, in some ways, revolutionary world? Or is it really gone for good?

I describe in the book the scene in the 1800s in New York, when factions supporting rival actors playing Macbeth began to fight each other in the streets, resulting in a number of deaths. If only audiences cared so much today about the theatre! But today when people are sitting at home in front of a thousand different screens, we can’t reproduce that time, when sitting in a theatre meant so much, gave people a taste of home, let them hear their past, their homeland… It was an incredibly vibrant time, when New York was flooded with immigrants, desperate to learn and prosper. In a startlingly short time, many of them did.

This is a book not only about your great-grandfather, but also about your extended family, and about you. It’s about your hybrid identity (half-gentile, half-Jewish). It’s about the family silence surrounding the one great, but somehow shameful family member. It’s about the discovery of roots, and the drawing of a line back to the other writer in the clan. How important to this story is the fact that you are Gordin’s great-granddaughter? Talk a little about the decision to write a book that was a work of creative nonfiction, infused with the writerly gaze and experience, rather than a “straight” biography.

I had a big technical problem writing the book, which was never really resolved – that it was, in fact, two books. The first was the scholarly Gordin biography that was needed because there wasn’t one – detailing the history of the man and his plays. The other book, the one that really interested me, was the family story and my connection to him and to his life. I got trapped in the biography, loaded down with facts and names and dates, and then did my best to bring life to all that with the personal stories.

The problem was that the resulting manuscript was too weighty and scholarly for the mainstream publishers, where my New York agent first sent the book, and too personal and informal for the university presses, which wanted a dry biography with footnotes and no personal material. Footnotes! I’d been doing research for over 20 years, most of them as a single mother in chaos, I had paper stuffed into boxes all over my house with no idea where I’d found this quote or that bit of play, and no desire to spend years digging it all back up. I said no footnotes, which meant most university presses were not interested.

Luckily, Syracuse was happy to take the manuscript and turned out a beautiful book, though I had to cut some of the personal stuff. If I had to do it again, I might try to actually do two books – one for the university Yiddish departments, with just cold facts, and another with far fewer facts but more heart and soul about the family.

A wealthy friend of mine, after reading the book, said, “Too much detail. Why didn’t you turn it into fiction? That would have been more fun and would have sold much better.” That may be true. But I have not the remotest interest in taking a fabulously interesting true story and fictionalizing it, inventing characters and situations when I’d hunted for decades to uncover the real ones. My friend Wayson Choy has written two novels and two memoirs; I admire that kind of ambidextrousness, switching between fiction and faction. I have no interest in even trying. Give me a true story, any day.

[Image: Courtesy of Beth Kaplan]